Maira Kalman is an illustrator, author, and graphic novelist. Her illustrated blog The Principles of Uncertainty, originally published through The New York Times, was collected as a graphic novel in 2007, and her illustrations have appeared in The New Yorker, Strunk & White, and The New York Times Magazine. Born in Tel Aviv, she now lives in New York City.

***

Interviewer: I know that along with writing And the Pursuit of Happiness and The Principles of Uncertainty, you’ve also worked in the past as an illustrator. Will Eisner makes a distinction between illustrations and what he calls “visuals”—he argues that an illustration “simply repeats the text,” while a visual is an image that actually performs some of the storytelling work. How did you become interested in making that move from illustration to graphic storytelling?

Kalman: It was clear to me, from a young age, that I would be a writer. Or that I wanted to be a writer. When I decided to stop writing (after college) and tell my story with drawings, I was still telling a story. My paintings are writing. And sometimes you don’t need to say anything at all, of course—just show the image.

But ideally they become one soup.

Interviewer: What is your writing process like when you’re working on illustrated blogs such as And the Pursuit of Happiness?

Kalman: I think of it as a book, not a blog. Did I mention I hate the word blog? It sounds like barf and blurt combined.

Anyway. Through visits to museums/sites/institutions, reading, research, sketching, note taking, photo taking and a general three-week immersion, I find my way to a story. I usually have a few hundred images that I need to edit down to about twenty or thirty. I know the important writing points and images. Then I weave the story together, changing the image order until it has a flow. Before I start to paint, I send the text to my editors for comments. There may be some shifts or changes. Then I paint and the text is handwritten on vellum overlays at The New York Times, so we can go over the text for mistakes. Very old fashioned. But a lovely process for all of us. At least for me.

Interviewer: I assumed you must prefer the term blog, since that’s how the The New York Times refers to it. They also refer to you as a visual columnist, and I’ve heard The Principles of Uncertainty referred to as a graphic novel, a memoir, and a sketchbook. Do any of these labels seem appropriate to you?

Kalman: Visual columnist is excellent. A visual memoir is also good.

Interviewer: Both And the Pursuit of Happiness and The Principles of Uncertainty involved a variety of artwork—paintings, drawings, photography—sometimes even photographs of complete strangers as they were crossing an intersection, or walking through a park. How do New Yorkers react when they notice you’ve taken their picture?

Kalman: Most people are fine with it. Some I ask, and they refuse. Sometimes (rarely) I snap without asking and they are irked and once in a blue moon irate. Usually (because it is true) I tell people that they look splendid and I would like to photograph them for my artwork. And usually people are pleased.

Interviewer: Do you still use a Leica?

Kalman: The dog ate the Leica a long time ago.

I use a Lumix digital camera. Small and snappy.

Interviewer: Where do you write?

Kalman: I write random bits in my sketchbook every day. Notes. Eclectic information. Lists. Sentences that I have heard. Quotes. But the writing I do for my work comes only on deadline.

Rituals. The room has to be in order. Everything in its place. There are procrastination rituals. Washing the dishes. Etc. But I think of those acts as clearing the mind while water is running. Like working near a stream.

Interviewer: Your columns have an incredible readership—your first column for And The Pursuit of Happiness, for example, had over 1,000 comments. Do you read the comments posted in response to your columns? Have they influenced your work?

Kalman: I was opposed to having comments. I thought they were completely unnecessary.

They may be good for the paper to gage popularity—and I am happy for that. I read some in the beginning and saw the overwhelmingly positive response—and I am happy for that (maybe).

But as input into my work—absolutely not. I do not want to hear excessive praise or excessive criticism. I rely on the response of my editors and the people that I know and respect. But other than that, the process needs to be private. And that is the way I want to work. It would be sad and scary to make work in response to a public opinion.

Interviewer: What influences led you to your words-plus-images style of storytelling? Did you read any comics growing up?

Kalman: I never think (thought) of comics as an influence in the words-plus-images thing. I did read Archie Comics of course. But that is pretty much it.

The words-plus-images comes from illustrated children’s books (Ludwig Bemelmans, Lewis Carroll) on one end of the spectrum, and Dadaist work, Saul Steinberg, etc., on the other. But of course they are all the same. The best of the children’s book world is very much in the adult world. There is also the work of Charlotte Salomon, who told her family story in gouache and text. I adore her work.

What did I love as a child? Penmanship. Making the letter forms over and over again with my Parker ballpoint pen. The drawing came later. After the writing.

Interviewer: You’ve said that you first knew you wanted to be a writer when you were nine or ten, that you were reading a book in a tree and suddenly you just knew. What was that experience like? It sounds similar to Haruki Murakami’s story, although he was watching a baseball game instead of sitting in a tree.

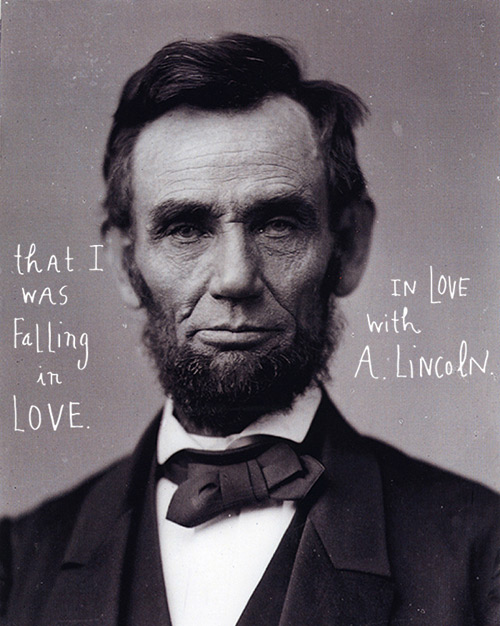

Kalman: It is completely impossible to say. It is like falling in love. Only perhaps more reliable. The feeling. Some earthly vibration that happens and you know that these are the elements that must play a role in your life. There is a certainty. Like your chemistry is right when you do those things. Like you are definitely you when you do them.

It does not eliminate confusion and fear. But confusion and fear are accompanied by certainty and delight.

Interviewer: You’ve also attributed your choice to be a writer to your seventh grade teacher, Miss Walters. Have you kept in touch with her at all as your career as a writer and artist evolved? Does she read your work?

Kalman: Oh dear Miss Walters. No, I never saw her again. She is a vision in my memory. It would be quite wonderful to contact her. What a good reminder.

Interviewer: Why did you stop writing after NYU?

Kalman: Well. I was writing since I was a young girl. Twelve or so. And the writing became more angst ridden as I traveled into my late teens. Writing brought out the sadness and despair. Not always, but often enough so that I thought it was awful. Maybe it was awful. Or maybe not. But I’d had enough of purple prose. It was better and more fun and funnier to draw the story. A fresh way to talk.

Interviewer: Had you studied writing at NYU?

Kalman: I went to NYU for literature. Attended very inconsistently. Spent much time in coffee shops staring at people. Then dropped out in junior year or something like that.

I did not study art. Took a few courses here and there. Mostly went to museums and started a library of art and photography books.

Interviewer: Why did you drop out?

Kalman: I was young and stupid. It was the late 60’s. Cultural revolution in the air. Tibor [Kalman] had joined SDS and was busy trying to change the world. I was writing poetry and knitting and sitting in cafes. I just was not interested in taking normal courses. Very bored. Or confused. Or dreaming.

My parents were not involved in my decisions. So I left NYU and then went back and out and pingponging, never to graduate. I actually think I probably need only small number of points to graduate. Not tempted though. Instead of going to class, I started to draw and then made a portfolio and then went to magazines.

So in a way it all worked out. Scary. Luck is essential.

Interviewer: Had you been working on art when you were younger too?

Kalman: I didn’t consider art my domain. But of course drew in school. Then after NYU it was a startling and pleasant idea. To draw.

Interviewer: Scott McCloud has defined art as “any human activity which doesn’t grow out of either of our species’ two basic instincts: survival and reproduction.” Does that seem accurate to you?

Kalman: On some level, art is about survival. So I am not sure it is not a basic instinct.

Interviewer: You’ve worked in a variety of mediums—set designs, fabric designs, storefront windows, postcards, your illustrations for Strunk & White, your New Yorker covers, a dozen children’s books. Is it difficult for you to move from one medium to the next? Do you have to approach a Kate Spade purse differently than you would a postcard, say, or an illustration for a magazine?

Kalman: The subject changes, but the person is still the person. I don’t think differently, but the situation defines part of the content. There is a feeling to each job. Or an idea that pops up. But of course you can see that the same person is doing these different mediums. It is me solving a problem in a way that seems appropriate.

Interviewer: Your children’s books experiment with their form as well—Swami on Rye: Max in India, for example, contains a maze-like sentence in which the reader is led from word to word by crisscrossing arrows, and a “two-headed chap” that talks in staggered left-aligned right-aligned sentences.

Considering it’s a children’s book, Max also uses a rather sophisticated vocabulary—words like “credenzas,” “unmutterables,” “saffron,” “soothsayers,” and “dervish.” Was it difficult to convince your publisher to print a children’s book with such a difficult word list?

Kalman: No, not at all difficult. The feeling is parents are reading to kids, and then kids hear these words that may sound enchanting (one hopes). The parents are interested and the kids are interested (again, one hopes). My editors really gave (give) me amazing freedom. The early years Regina Hayes for the Max books. Nancy Paulsen is still my editor at Putnam’s. So I was lucky to meet people who wanted to do something a little different.

Interviewer: Are you working on a new project now that you’ve finished your year with And the Pursuit of Happiness?

Kalman: Happily many projects. Hopefully not too many.

Just finished illustrating a children’s book written by Lemony Snicket called 13 Words—coming out next fall.

Will start illustrating a young adult book with Daniel Handler (Lemony).

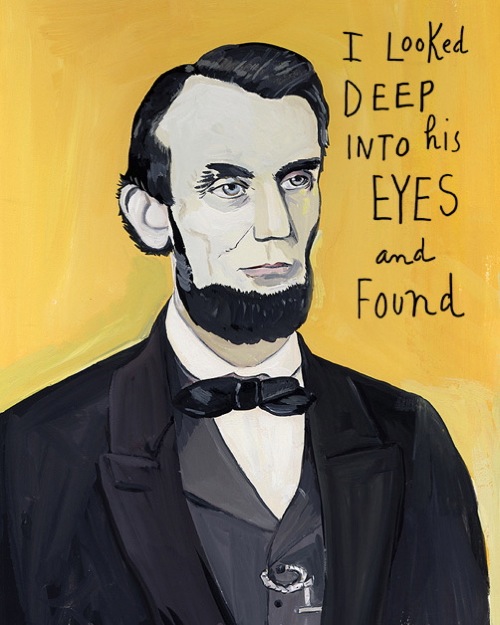

Taking the Lincoln column from Pursuit and making it into a children’s book.

Pursuit is being compiled and will also be a book next fall.

Working on wallpaper for MAHARAM.

Random articles for magazines.

Teaching again. A mini seminar in the School of Visual Arts Graduate Division.

And some other smaller things that I can’t think of right now.

A nice mix.

Interviewer: You’re working with Lemony Snicket, you’ve worked with David Byrne of Talking Heads. Do you find collaborating on writing/illustrating projects is different than working on the ones you do on your own?

Kalman: I worked with my late husband Tibor Kalman on hundreds of projects. With Rick Meyerowitz on New Yorker and The New York Times pieces. The process is actually quite similar. It requires an ability to be honest and open at the same time. Ideas are thrown into the pot and edited out. I can work with people who have a really good sense of humor and sense of language.

Interviewer: What originally led you to produce a yearlong column on American democracy?

Kalman: The editors at The New York Times—David Shipley and Mary Duenwald—wanted me to create another column. We decided that it would be interesting to be more journalistic than introspective. Obama had just been elected and we were all excited about the new feeling in the country. And I knew nothing about history and politics. So it seemed like a good time to look at that. Just get thrown into a subject and swim around collecting impressions and ideas.

Interviewer: Despite that they share their form, was working on And the Pursuit of Happiness a different experience than working on The Principles of Uncertainty?

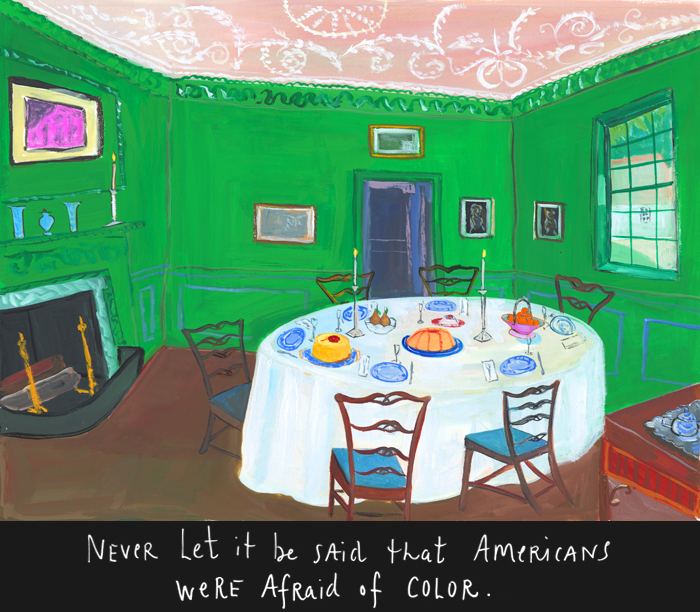

Kalman: Yes. Pursuit was all about journalism and research, interviews, traveling and trying to absorb a foreign subject. It had to be a bit educational. But a delight to do.

Interviewer: What did you learn while working on Pursuit?

Kalman: I learned that things are so complicated it is impossible for me to understand or judge. I gained an appreciation and profound respect for the genius founders of this country and what they envisioned and created. And I gained respect for the people (at least some) that are in politics. Along with an incredulity that anyone could be in government or politics.

I found out that a year was just about right for delving into that subject for me. I feel fresh and ready to plunge into something else.

Interviewer: Chris Ware has written that “people can hardly form sentences that make any sense anymore; they’re making nouns into verbs, and acronyming words out of the first letters of a lot of other words, and using words wrong all the time to mean things that they don’t. So I guess little pictures are about the only way we’re going to be able to tell stuff in the future, since most anybody can understand them. I think it’ll be good, because people like looking at pictures, and I think words have had their day, anyway.” Do you think words have a future on their own? Or are their days numbered, unless they’re teaming up with images?

Kalman: For the time being, in my opinion, words are much more important than images. If you have images and words and the images are good but the words are not, it is a failure. The content, the ideas, the expression, the human connection—all that is inherent in writing is what is truly important. The rest is icing on the cake. It is grand icing. It is essential icing. But the writing comes first.

As for the future. I am not a fortuneteller. And I can’t stand predictions.

Read Maira Kalman’s visual column And the Pursuit of Happiness, to be collected as a graphic novel in October 2010, at kalman.blogs.nytimes.com