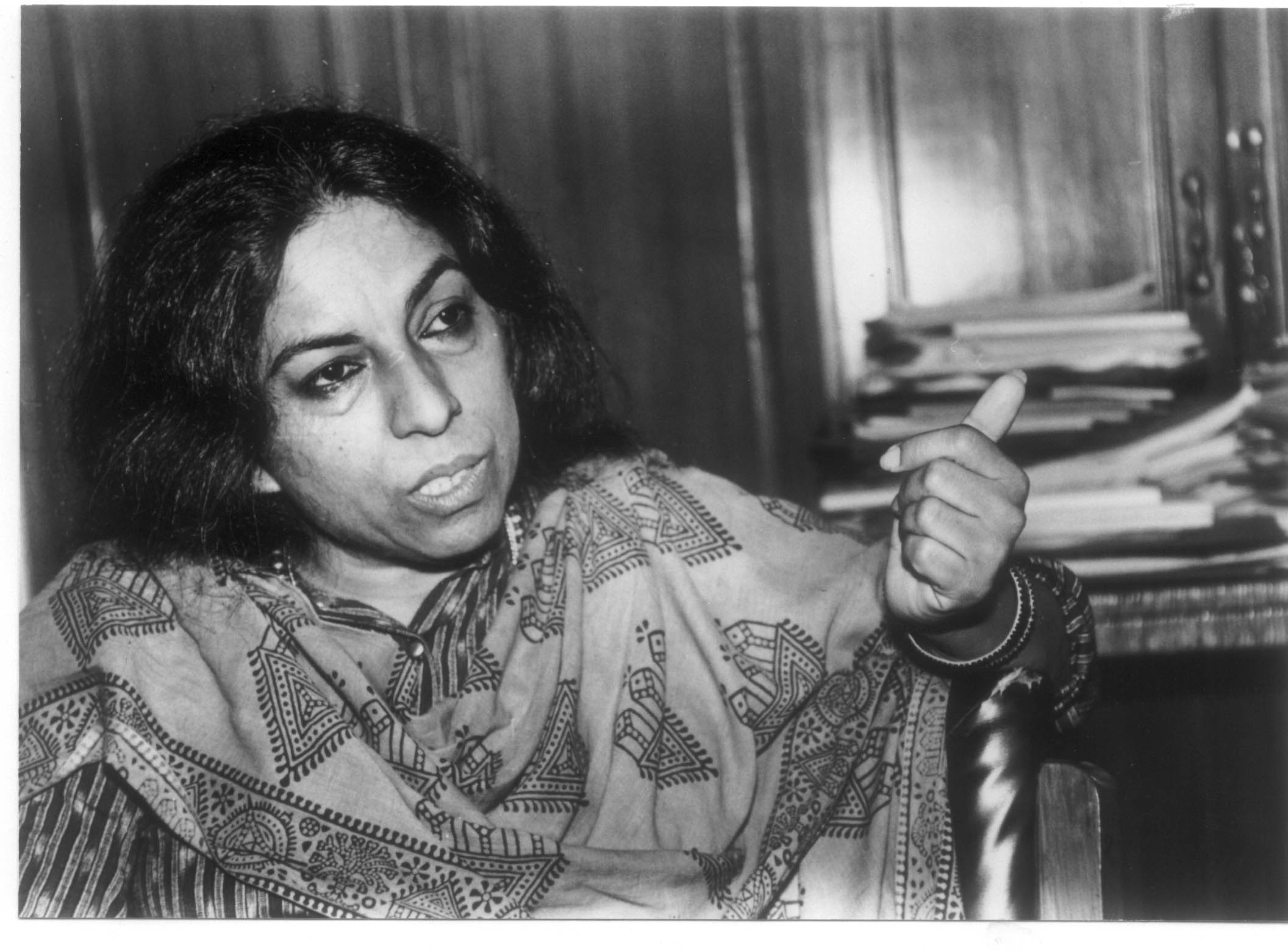

Urvashi Butalia is the founder of Zubaan Books, a self proclaimed feminist publishing house based in New Delhi. Butalia has been publishing academic texts, children’s books and fiction by women for over 30 years, and is widely regarded as the founder of the feminist literary movement within India. Zubaan has published countless global best sellers including, most recently, Vandana Singh’s collection of short stories The Woman Who Though She Was a Planet, which was heavily praised by Ursula Le Guin. On June 26th, 2014 Urvashi and I met in Zubaan’s Shahpur Jat, New Delhi office. Below is our conversation.

***

Interviewer: What year did you start Zubaan and under what circumstances?

Urvashi Butalia: Well, Zubaan evolved out of Kali and I started Kali in 1984 with Ritu Menon. In 2003 Ritu and I stopped working together so that is when I founded Zubaan. Thus even though its currently Zubaan’s 11th anniversary, we are really celebrating our 30th anniversary because Zubaan was a child of Kali. We are the same people with the same mission. The name just changed. The circumstances under which I started Kali, and subsequently Zubaan, require a bit of background. When I was at university it was a time of great political turbulence in India. I became heavily involved in student political groups. I graduated from Delhi University with a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in literature, but Delhi University was still very much a colonial institution then, in the sense that we did not study our own heritage. For example, studying literature essentially meant that you were studying English literature, and there were hardly any Indian writers, so while I had finished my master’s in literature, I felt that the subject I was studying, even though I loved it, was incredibly far off from the reality that I was living. I was determined not to do the predictable thing, which was to teach, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I had this great dream of wanting to set up a little printing press in my house where I would print radical political pamphlets and feminist texts and other books and then I fell into a job in publishing completely by accident. A friend of mine worked with Oxford University Press, and she said, why don’t you come and do some freelance work and so I went and did that and instantly fell in love with it. I decided that it was what I wanted to do. And, as it happened, Oxford University Press offered me a trainee position. So that was really the start of my love affair with publishing. At the same time I was working at Oxford University Press, I was becoming more and more involved in feminism and feminist activism. I felt that there was a need to better understand many of the issues we, as feminists, had been working with but we had no literature. Nothing that could help us. Absolutely nothing to work with. And we were facing issues like the fact that dowry was growing by leaps and bounds. Where was it coming from? And what were its sociological roots? What was all this about? So I talked with my bosses at Oxford University Press who were great, very nice people, and said to them, why don’t we do some books by women, about women? And they didn’t seem to be all that interested. They asked, how do women write? And what do they write about? So then I thought, okay, if they won’t do it, I’ll do it myself. And that was just a very simple reaction thought. But then the idea started to really form in my head and I started to work towards actually doing it. I left my job at Oxford University Press in 1978 and I actually started Kali in ’84, so there was a six-year gap in between during which I was working in a teaching job, but the idea of a press was also gestating and forming more completely in my mind. And that is really how it came about. I wanted to answer the needs of the movement. And then as we began to publish we began to realize exactly how important a role literature would play. Listening to peoples’ narratives and just paying attention to people was something I did innately. So when we started Kali that seemed to be the direction to go. Even though we wanted to go wholeheartedly in that direction, we knew that was a direction that was not going to make us any money, so we published many research-based books, many academic books, etc., to generate income and then we put that income towards activist books. Those were the beginnings.

By virtue of being a self-proclaimed feminist publishing house, Zubaan is asserting something some would regard as fairly radical: narrative and story have both political and social power. How do you think narrative power functions? What were some of the first books you read or stories you were told that convinced you of the power of story?

There are many people and many stories from which I first understood the power of narrative. I learned the power of narrative from our mothers. They were a generation of women who were involved in the nationalist movement. They fought alongside Gandhi and Nehru and they were very inspired by the ideal of India. Many of these women took to feminism. There were many of them who were peasant leaders. Growing up and just listening to their stories, seeing history through their eyes was really important for me. One of the earliest books we actually published with Kali was a book of oral histories of women in the Telangana Movement, which was an independence movement in Andhra in the 40s. From my mother and grandmother I heard stories about what had happened to women during the partition and how they had dealt with that time. They had to rebuild their houses. Also, inside my college and university there were single women who had not gotten married because of the upheaval of partition. Their marriages would have been arranged. But these unmarried women went and made something of their lives in a completely different way. It was from all of these women that I learned about the transformative potential of experience. Experiences that would otherwise be very terrible and negative, like a violent conflict, empowered these women. There were many stories like that. I was also influenced by women like Pandita Ramabai, one of the first women to travel abroad from India. She was called Pandita because she was very, very learned, and she was an upper caste woman who married a lower caste man. And then she converted to Christianity, giving everybody a deep shock. Her experiments with religion and trying to understand what religion meant for women inspired me. There was also a woman named Rakhma Bai who was a child bride and who refused to go to her husband. She said she had been married against her will and that she would not go to him. The husband filed a case against her which became very famous in the British courts. In the end, the courts ordered her to rejoin her husband and she refused. These were all Maharashtrian women but there are many others. There are so many stories like this. This other women who was called Tarabai Shinde wrote this amazing text, which in fact I have right here, called Stree Purush Tulana or in English, A Comparison Between Women and Men, in which she really lambastes patriarchy and says what do you men think you are? These were the stories we grew up with. And then there were the stories that we read from the outside. For example, I was very inspired by a South African woman who is now dead, named Ellen Kuzwayo, who wrote a memoir about the apartheid days. I have also been immensely moved by women like Toni Morrison, Angela Davis and Petra Kelly, through their writings and by hearing them speak. I was also greatly influenced by Audre Lorde. I remember meeting her in 1984. I listened to her speak and it was quite amazing. In this way I have hundreds of foremothers who has taken up the banner before me.

Zubaan literally means tongue in Hindi, but it has many other meanings, such as voice, language, speech and dialect. The varied meanings of Zubaan points to the duality and limitations of language itself. As someone who has heavily invested in the power of the written word, what do you see as language’s greatest strengths as a medium? What are its shortfalls?

We are constrained by language in many ways. We choose to publish in English so to me that is the first constraint. We choose to publish in English partly because it is the language in which we are most competent. My colleagues and I are based in Delhi. It is also the language that allows us and our office some international access. In the days of Kali we also published in Hindi, but I think it was the wrong moment for the Hindi market at that time. The market was not ready and it was not an easily accessible market. It is much better now. And we have often thought of going back to publishing in Hindi, but now all the big houses are starting to publish in Hindi and the competition is of a different nature so we would have to consider it carefully. So in one sense we are constrained by our choice of language, which means that we cannot really reach out across India, which is an incredibly multilingual country where language politics are very prominent. We do work very closely with publishers in other Indian languages to have our books translated. But I think there are politics beyond languages. Because when you are looking at the writings of women, or any marginalized group, what you are dealing with is very deep silences about certain things. You are dealing with a lack of vocabulary to express certain things. You are dealing with an inability and you are dealing with a lack of receptivity in the society as a whole. I think of someone like my grandmother, for example, who had to live through a terrible time and who had no one to speak to. I sometimes talk to my aunt about her, and my aunt says, you know, she was a bit mad. She would throw her clothes off and become naked. And then I was talking to another friend of mine about her grandmother, and she said, you know as kids we just ignored her because she was always in the attic room, just muttering something. The thing is, these women, where they mad? Or is it that they had something to say that was so disturbing, and of such depth that they didn’t have the words to say it? They knew no one would have listened. So how do you draw these stories out of these women? That to me is a very important part of our work. Which means working in ways and focusing on things that an ordinary publisher wouldn’t focus on. You know, we don’t only go out and commission manuscripts or receive manuscripts. We struggle with authors to help them write their works and find their words. Another limitation of language is that it is so easy to be sitting in Delhi and to be publishing works written by women in English. We inevitably end up publishing work by upper-class or middle-class educated women. But that is not what we are about. So how does one go beyond that? How does one publish works by women who do not have language, who are not literate, who cannot write their own stories? A few years ago, in 2006, we published a memoir of a domestic worker named Baby Halder who had a very terrible life. She desperately wanted to study, and finally was helped by a kind employer to learn to read and wrote the story of her life, which, incredibly, became one of our best-selling books. The name of the book is A Life Less Ordinary. And this transformed her life. She now thinks of herself as a writer and has written three other books. She is an icon for thousands of other domestic workers across the country, She gives talks and has inspired many others to write the stories of their lives. That is the kind of publishing that, to me, is really important. And that is what I mean by the limits of language.

What power does a storyteller have? How do the stories we know affect our understanding of the world and ourselves?

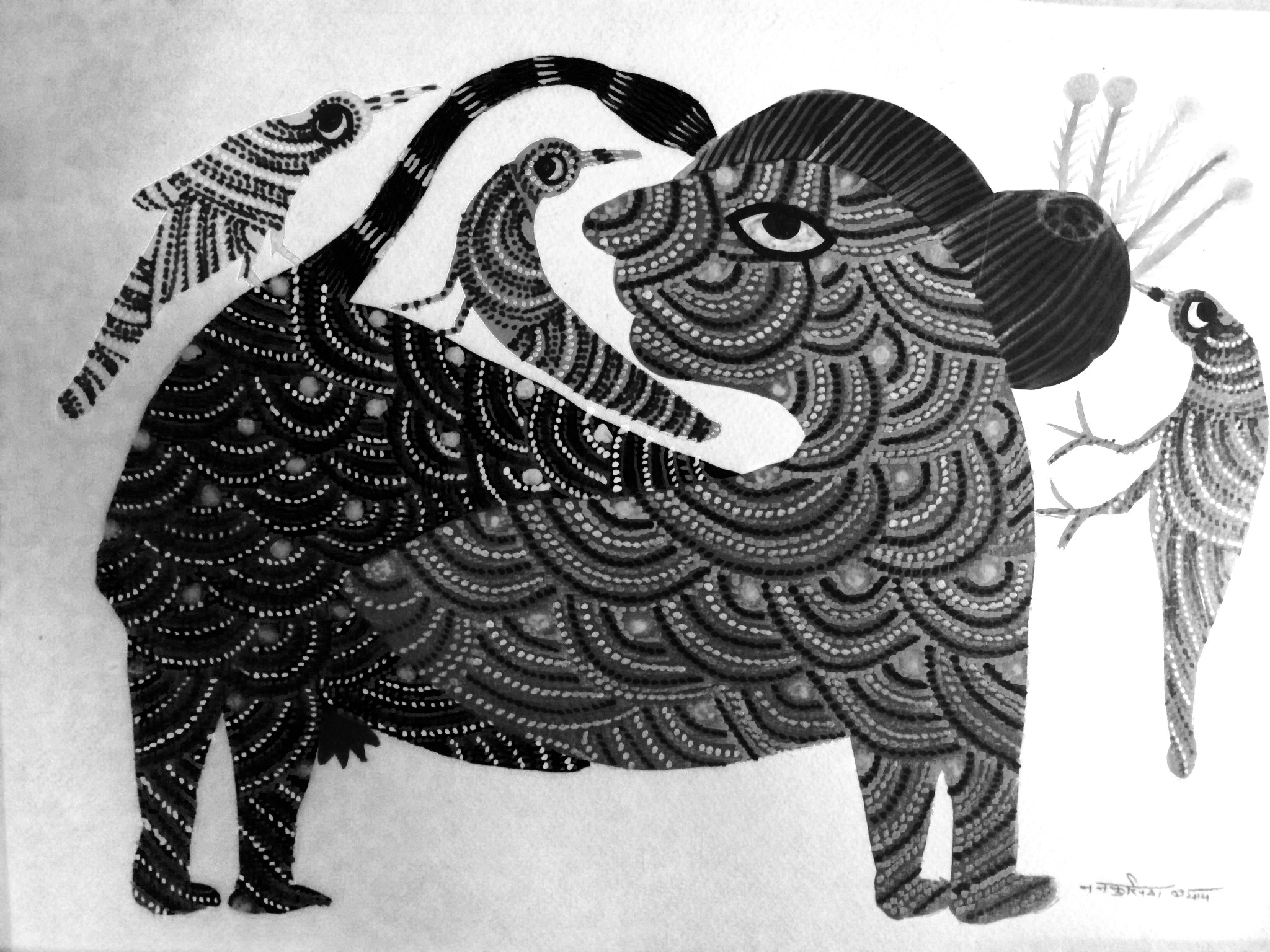

I have two other examples of powerful storytellers. Each one is very different. When we were still Kali, we were approached in 1987 by a group of women from Rajasthan. They came to us with a book project. They were all village women. They were accompanied by three activists who were part of a program called The Women’s Development Program. In the program, the village women had done some health workshops and, as part of the workshop, created a book in Hindi called Shareer ki Jaankari, which means Know Your Body. The book focuses on how a female’s life changes from youth to old age. And the village women wanted to have the book published but the program people said, no we can’t publish this, it’s too pornographic. This book was about the body, it was about menstruation, it was about sex, it was about white discharge, and so on and so forth. But then the women brought this book to us and said, “Will you publish it for us?” and we were so excited about it because it was village women. It was the kind of book that we, in feminist publishing, dreamed about. So of course we said yes, we’ll publish it. But they said they had some conditions and one of the conditions was that there were 75 of them who had created the book and all of them wanted to be featured as authors on the cover. So we agreed to that and I’ll show you how we did it. We did it on the back cover and through some very creative book design did, indeed, include all 75 names. The other wonderful thing was that they told us all these wonderful stories which became part of the lore of us getting this book published. When they had initially done the book they had drawn the naked body in it. A naked woman and a naked man side by side because it was, after all, about the body. But they tested this copy of the book in the village and the villagers said this is all rubbish, you’d never see a naked person in a village like this and this should be true to reality so they went back and rethought how to present this and came up with the most ingenious solution. For example, they a drew a woman completely covered from head to toe, like you would see her in a village, and then there is a little flap in her skirt which you lift up and can see how she is made from the inside and little flaps on her chest that you open to see her breasts and then you cover them up and she is still modest. This was the most amazing, inventive solution. So we published this book and today we have sold maybe 70,000 or 80,000 copies, I have lost count, and we have never sold one copy in a bookshop. It is only ever sold through village women who just take it as their book and do what ever they want with it. It is the most amazing book. It has been pirated, translated into other languages without our consent, but we don’t care. We don’t make money from it, but we don’t lose money from it, but it is the kind of publishing that nobody else would do because they don’t have that ideological commitment to it.

The second story is the story of a woman named Salma who is from Tamil Nadu. We published a novel of hers and a collection of her short stories. And her story is very interesting. She comes from a very tightly knit, conservative Muslim community in Tamil Nadu and she was pulled out of school when she started menstruating and kept at home, ready to be married. She was married at age 19 or 20 and her husband was a political activist and he had been standing for village elections. After she was married she was locked up in the house and kept veiled and all this time she was secretly writing erotic poetry, which she desperately wanted to study. Her brother was smuggling books in to her, which she was reading and her mother was smuggling her poems out and having them published under a pseudonym, which was Salma. Her real name is Rokkaiah. And then what happened is that this federal amendment in India was made in 1992 and it mandated that a certain percentage of elected posts at village municipal levels had to be women candidates and her village became a village where only a woman could stand for election. So her husband tried to persuade every other woman in his family to run, convinced that if they won it would give him more power. But they all refused. So he had no choice but to nominate his wife, Rokkaiah, because he didn’t want to lose his power. She agreed to stand for election and the first thing that happened is she took off her veil, because you can’t win a political election if no one can see your face, and she won the election and became a very successful politician. Then she moved from the village to the state level and during this time she wrote her book which made her world famous. Today she is recognized around the world as a poet, writer, novelist and politician and thus for all of the women around her Salma is really an inspiration. She does many talks for women who are thinking of having a political career, and tells them what hard work it is, how disappointing it can be, and I have seen her at these talks and it is really an amazing conversation that she has with these women. So for her, her narrative moves much beyond the actual book, and has become a part of something else entirely.

What do you think differentiates the modern feminist movement in India from feminist movements in other parts of the world?

This is a very difficult question to answer. There isn’t one Indian feminist movement. There are many, many Indian feminist movements. What you see is generally the visible, articulate Indian feminist movement but there is, in fact, much more going on. I think that activism remains very strong here even though the modes of resistance may have changed. In my day, every day there was a street level demonstration. Now you see demonstrations when there is a campaign, but it isn’t an everyday affair. But I think there is a way in which feminisms in India, and the whole of South Asia, are very linked to ground realities in a way that they aren’t in the West. You will not find separate feminist movements for the environment or caste or dislocation or nuclear issues. All of these movements are very real to feminists in India. I also think there is a unique openness to learning. And I think fortunately, even though there have been deep divisions among Indian feminists, we have not as of yet had the sort of divisions that act as barriers and don’t allow us to talk across those barriers in the ways in which very often the dialogue between white American feminists and black American feminists in the West are unable to talk. I know that this division has been very difficult. But here in India it is not that the difficulties aren’t here, I don’t want to make it sound all romantic, because it’s not. The dalit (untouchable) women in the caste movement feel very marginalized by what they see in the supposed mainstream movement. Indian women of alternative sexualities and minority religions often feel this alienation as well. These questions have been raised from within in a process that keeps the dialogue open. So there has never been a moment in which these feminisms aren’t talking to each other, aren’t communicating. And I think that is very important. There is an awareness here which I find lacking in the West, which is perhaps a gross generalization to make, but perhaps interesting to note, that there is an awareness here that there are other feminisms out there and that we need to recognize and understand them. We recognize that our feminism is not the only feminism. This is a very opposite mindset from the West in which people are always making statements about India, and how terrible the country is towards its women, and how Indian feminists are where we were 50 years ago, as if it is a kind of race in which someone is ahead and someone is behind. People do say these things. It does happen. And I think here in India there is a different mentality. There is a greater understanding of differences perhaps because we are a country that has learned to understand difference. It is not that we don’t acknowledge a hierarchy. It is true that our feminism is also very hierarchical. It is not that it isn’t. It is not free of these struggles. But at least there has always been awareness and a discussion.

What role do you see fiction, specifically, playing in this movement?

It is an interesting thing. I think in many ways Indian women have redefined what Indian fiction means. If you look at the novels written by dalit (untouchable) women and many others there is a way in which their life story becomes the template for the story of their communities. These women’s stories are based on their own lives, but they are also based on the life of their community. Their stories are the narratives of oppression. They tell a story of bravery. They tell a story of courage that is, on the face of it, fiction, but it is really something else. These works allow a reader to enter a reality which a sociological treatise or a political speech cannot do. We publish a lot of books from writers from the Northeast of India and these writings are completely immersed in the conflict that that region is caught up in. The conflict is never absent from these works. And yet they are deeply moving stories, and we have found that these stories have become like torches. These stories, people have taken them and they have become movers in political action. There is one story, for example, by a writer named Temsula Ao. She is a Naga writer. The story is called “The Last Song.” In the story a young woman is raped by an army man, and the only thing she knows how to do is sing. She sings beautifully, and she keeps on singing as he is raping her and she dies in that violent rape and then the hills around her, where she lives, are haunted by her song. It is just the most amazingly moving story and it has become something that has gone much, much beyond. It is taught in schools now, it is taught in colleges. The ways in which women have redefined fiction out of their experience of living in the areas that they have lived in, that is, to me, the first step. And this enables fiction to reach further than what research work might do, and to reach a different audience which is often made up of young people, city people who don’t know anything about these realities but will get a sense of them through the stories. So we do a lot of that. And it is really quite, quite inspirational. I mean, the days when people said a story must not have a political message, that a story is not the same thing as standing on a soapbox and pounding your chest and making a screech, I think these days are over. It is true that one doesn’t have to use a fictional story to communicate a political message, but the politics cannot be kept out. The politics that you live and grow up in will enter a story, whether you like it or not, and I think this so enriches story telling. For us, as publishers, it is really moving.