Paula pulled out all the drawers in her dresser and shook them empty, one by one, over her bed. There were hundreds of letters, perhaps a thousand, each decorated with large international stamps of foreign origin and several overlapping faded postmarks. They were green and yellow and white and red. They were most of them small, the letters inside folded over themselves several times. There was another pile on top of the dresser in a Reebok shoe-box—the dozen or twenty letters to which she had found the time to reply.

She was looking for Ben Bartlett’s letters. Ben was back from the war and he had a purple heart. Nobody agreed on where or how severely he had been wounded. According to some, he came back without legs. According to others, he’d been shot through the hip, and while the bone was shattered the rest of him was fine. There was a rumor he had lost his hand and now there was a hook in its place. Some said it was only a finger.

Whatever Ben was missing, there was one point on which everyone agreed: He was looking for Paula.

The letters had started coming a year before. At first they were a trickle. John Kottke sent her missives from the western front, describing his nightmares and erotic dreams, all featuring her (or parts of her body). He did not discuss the war. She wrote back the first two times, offering encouragement and enclosing a picture. Ernie Carmichael wrote her next, explaining that though they had not met, he felt very close to her ever since John Kottke had shown him the picture, which featured Paula in her favorite bikini, the cups drawn aside, her breasts exposed, the nipples swollen and blushing from pinching. She wrote him back once to thank him for his compliments, and the picture he had sent her. It did not depict his body, but a dead man of Asiatic appearance, blood running thick and black from his nostrils and ears.

Then Peter Crenshaw started to write her, and Marcus White, and Nathan Reagan, and more, and more. Some she knew from school. Others were distant cousins, who explained their familial connections with an obsessive care for detail better suited to a fetish. The rest were perfect strangers. They told her about their kills, about the atrocities they saw the enemy commit in clay huts and tin villages, about what they would do to her when they came home.

She truly meant to write them all back. She sent them pictures when they asked. Once, she bent over on the floor in her room, displaying herself for the long free-standing mirror, her heels pressed up against the glass. She aimed the camera behind her, holding it up and backwards over her head, her arm trembling from the camera’s weight and weird angle. She held herself open with the other hand and snapped the picture. They liked that one. The letters came pouring, torrential. Come-stained and smelling of strange bodies. She didn’t have time to read them all anymore. She stopped trying and started stuffing them into her dresser drawers, where she imagined them whispering to one another in the dark, while she slept. She imagined them waiting for her, all full of longing and malice.

Half her boys or more would probably die before they could come home. John Kottke stopped sending letters right around the time Ben Bartlett began.

After an hour of searching, Paula was pretty sure she had found most of Ben’s letters. There were nine of them stacked up on her pillow, each at least half an inch thick, swollen with his correspondence. She rubbed her hands dry on the front of her dress and shoveled the rest back into her drawers. She slid the drawers into the dresser. The big drawer at the top pinched her finger. It felt as if the blood and meat would swell until the skin burst and peeled away around them.

Paula left the letters on her bed. She would read them when the pain stopped.

*

Paula worked at the library. She shelved books. When she came in to work the next afternoon, after school, the clerks at the desk asked her where she had been. Lisa, the tall one, was clutching a bouquet of flowers—orange roses and long baby’s breath wrapped in glossy green paper.

“I’ve been at school,” she said.

“He came looking for you,” said Sylvia, the squat one with a mole on her earlobe where an earring should be. “He asked us where you were.”

“We didn’t know where you were,” said Lisa, behind the flowers.

“We said you’d be coming in later,” said Sylvia. “He said he had to visit with his family. He said he’d try again later.”

“He left you these,” said Lisa. “Make sure to cut the stems.” She handed the bouquet across the desk.

Paula took the flowers back behind the desk, where the books piled up and waited for her to shelve them. There was a card among the stems. It said, Flowers for my flower. I’ve been waiting so long.

She slipped the card inside a book about the social lives of bees. She shelved the book out of place, among the histories of artillery. At five she called her mother and asked her to bring the car. “Please come pick me up,” she said. “I feel ill.”

“Your shift’s not done yet,” said her mother.

“I want to go home.”

“Well, alright,” said her mother, “but it doesn’t mean we’ll let you off rent for the month.”

“I know, Mom.”

Paula’s mother and father had been charging her a hundred dollars a month to live in their home ever since she turned eighteen. When she graduated high school she would have to pay more.

Paula sighed. She looked at her finger—at the loose flake of skin that still clung to the wound where the dresser had pinched her, and the blood that welled beneath.

*

It was her mother’s turn to decide what they would listen to on the radio. Her mother chose silence. Paula held the flowers underneath her nose and breathed them in. She watched the gas stations and the supermarkets roll by. It was getting to be dark. She said, “Is it true you’re supposed to cut the stems?”

“It helps them stay alive a little longer, if you put them in water,” said her mother. “You’ll never believe who’s waiting for you back home.”

“Not Ben Bartlett,” said Paula.

“And why not? You think you can do better than him?”

Paula shook her head.

“He’s a hero, Paula.”

“I know, Mom.”

“He’s got a purple heart now for what they did to him in the war.”

“I know.”

“Took his nose clean off,” said her mother. “Now you can see up the nostrils. He has a prosthetic but it hurts him to wear it. Try not to look too disgusted when you meet him. And for God’s sake don’t stare. Close your eyes when you kiss him.”

“I won’t stare, Mom.”

“We raised you better than that.”

Paula examined her pale reflection in the window. She said, “I always imagined myself with a soldier.”

“I know, dear.”

“I didn’t think it would be like this.”

Her mother’s mouth curled into a tight, painful smile. “What do you mean, like this?”

“Nothing,” said Paula. “I don’t know.”

*

When they got home his car was gone.

“What kind of car?” said Paula.

“An old jeep,” said her mother. “It was orange like a fire hydrant. I don’t know why you care.”

“It doesn’t really matter,” said Paula. “I just wanted to know.”

They found her father in the kitchen. He was swigging the dregs from a can of Miller. He tipped the beer back and drank till it was finished when he saw them. Paula watched his Adam’s apple climb his neck and tumble down again. There were twelve empty cans piled up around him on the table. Six in front of him, six on the opposite placemat.

“You just missed him,” he said. “We were talking all about you.”

There were family photo albums stacked up at the center of the table. The one on the top was open to a page of pictures from when they were younger, before her little sister came. There was a picture of the cake from her seventh birthday, and a picture of her father standing beside their first new car, a Honda, the deed in his hands. There was a picture of her in blue panties and nothing else, asleep on the couch, a stuffed cat in her arms.

“You showed him my little girl pictures?” said Paula. She lay the bouquet down on the counter and closed the album. She stacked them in her arms.

“Of course I did,” said her father. “If you’d been here for him when he came for you I wouldn’t have had to.”

Her mother took a tall glass from the cupboard and filled it halfway with water. She took a pair of shears to the stems of the bouquet while Paula watched and clutched the photo albums. She put the flowers in the tall glass and set it on top of the piled albums. “Go on,” she said. “You take these upstairs and put them where the sun can get them.”

Paula swayed slightly on her heels.

Her father said, “It was hard, keeping my eyes from the burns.”

“I thought it was his nose,” said Paula. She stood in silence, waiting for someone to answer. All she could see were the flowers. They were a field, swimming. Fuzzy blots of color. Nobody answered her.

*

She hid the albums beneath her bed. She put the flowers on her windowsill. She looked at herself in the mirror. Saw her camera. She put it in its box and hid the box in her garbage can.

She wondered how Ben could be everywhere she was. She had known that he would come for her, or in any case that one of them would. She hadn’t thought that it would be so soon. She hadn’t thought that it would be so strange. She had wanted to date civilian boys for a while, boys who didn’t know what it was like to bleed a man out. Not forever, but while she was young.

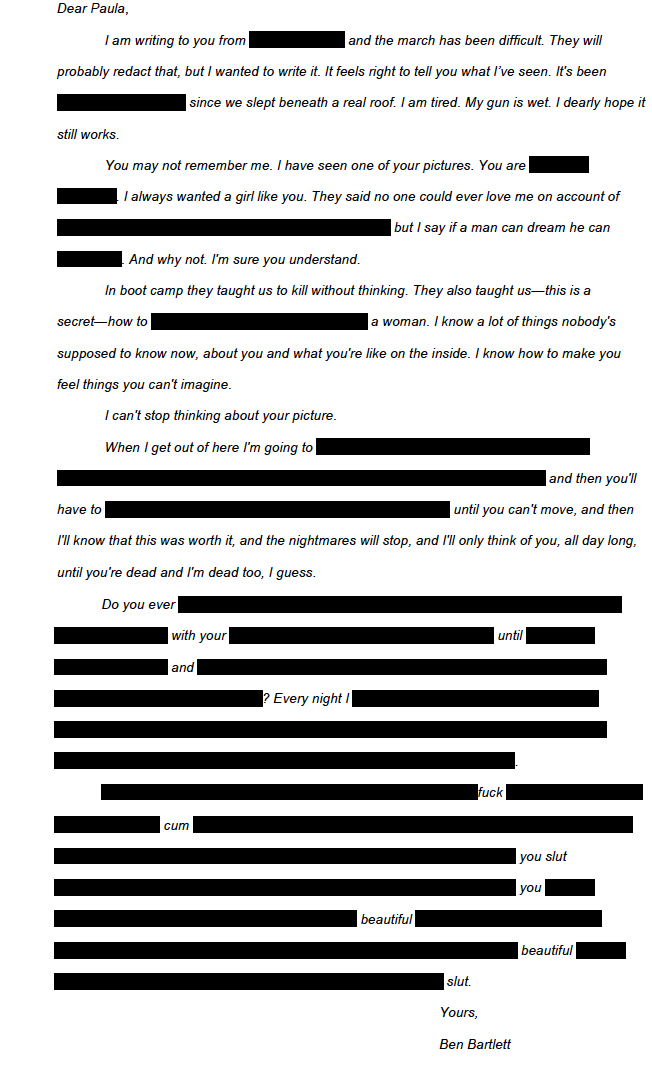

She opened Ben Bartlett’s first letter. She ran her finger over the heavy black ink of the redactions. It was cold, and still felt wet, but did not smear under her touch.

She closed her eyes and counted to ten. She made herself breathe. The sheets stuck to her body. She was covered in sweat. She was wet between her legs, yet her stomach churned with cold terror. She felt as if it might swell up inside her, as if it might burst out from her guts and grow and grow and grow, like the black ink, the redactions.

She folded the letter and put it back in its envelope.

She opened the next letter. A Polaroid fell out of the envelope. Someone had blacked it all out, excepting a grasping white hand in the foreground, reaching for something Paula couldn’t see. A hand with thick, hairy fingers and knuckles like tumors. It must have been his.

She traced her fingertip over the picture, felt the skin of the white arm. She could feel, though she could not see, that it had risen up in crawling, angry gooseflesh.

*

When she was sure her parents were both in bed for the night and the moon was high and full, Paula went out for a walk. She couldn’t sleep for thoughts of his body pressing on hers. Every time she closed her eyes she imagined Ben Bartlett kneeling over her in bed, his thighs between her thighs, a gun’s hungry muzzle pressed to her temple. Different parts of his body were disappearing and reappearing. She felt him move inside her, and when his cock disappeared and his trigger finger disappeared at the same time she would gouge his face with her nails, she would kick him away. And yet it was always one or the other. Or his face. Or his eyes, or his ear.

She wore baggy blue jeans and an orange hoodie with a zipper. She didn’t want to be noticed.

It was cold out. The breeze made her zipper rattle. The neighborhood strays were trotting the sidewalks, they were sniffing each other, they were looking for food. One of them must have been a drug dog before he was here. He was a German Shepherd. His coat was matted down in filth, yet his bearing was rigid, military—too cruel to be called proud, too proud to be stupid. He kicked a smaller dog—a fetal-looking Pomeranian—away with his left hind leg. She crossed the street to pass them. They yapped at her as she went.

When she turned the corner she saw an orange jeep on the side of the road, its passenger side wrapped around a lamppost, which leaned now toward the pavement. The whole jeep had bowed inward like a folding hand. It was flecked all over with rust. A real piece of shit. Beer cans were scattered across the asphalt and the pavement, half-empty, still fizzing, full and deeply dented, or crushed.

She walked toward the jeep. As she came closer she saw a figure in the night, a man hunched and limping. She couldn’t see him clearly—couldn’t count his legs, couldn’t find his arms. He was bleeding. The trail of blood shone glittering in the skewed streetlight. He was clutching himself.

He was walking toward her. Stumbling as if he was forced to make do with one leg. Or as if he had two but they were broken. He was a silhouette, bent and broken, somehow, somehow broken. He tilted his head as if to better see her through the veil of night. She could hear his labored breathing.

He said her name.

She ran.

*

The mailman was waiting at the front door. He wore a thick black mustache and Coke bottle glasses, which glinted in the moonlight. He held a box packaged in white wrapping paper and red ribbons. “Ben sent this to you,” he said.

She felt ill. Imagined the gun at her temple. The dick inside her disappearing and then coming back. Mobile bullet wounds. Wounds that she could see inside.

“And you’re bringing it now? It’s nearly three in the morning.”

“He sent it express,” said the mailman. “You need to sign.”

He put the package down on the sidewalk and handed her a clipboard. She thanked him and wrote her name. He walked away, his shadow boyish in its shorts and high-top sneakers.

She crept up the stairs to her room and opened the package. There was a card inside, atop a bundle wrapped in thin, pink paper. It said, A gown for my Cinderella. Meet me at the dance.

No one else had asked her to the dance. She had a reputation.

She unwrapped the bundle. It was a poodle skirt and a sheer white blouse.

She opened his third letter. It was all blacked out.

*

The next night, after refusing all day to let her leave the house for school or work or anything else she could think of, Paula’s mother drove her to the dance. “Are you on the pill?” she said. “You can be honest.”

“No Mom,” said Paula. She twisted a handkerchief in her fists. There was a dead bug broken open on the window, small and brown and blue.

“Well it’s too late to start now,” said her mother. “Whatever happens, remember, I don’t want to hear about it.”

“Yes Mom,” said Paula.

“And Paula,” said her mother. “Try not to look at his ear.”

“I thought it was burns,” said Paula.

Her mother turned on the defrost. The slow, low breathing of the car precluded conversation. Paula straightened her poodle skirt.

*

Ben Bartlett had an eye patch over his right eye. Otherwise he was whole. Paula recognized him now. She stepped into his open arms, as they began to rock together from side to side with the music and the high school thrall. They used to call him Benjamin. Then he was a puke, a grease, a skid mark. Now he wore a starchy uniform with sharp creases and a purple heart pinned to its broad, strong chest. His blond hair was cropped close to his skull, and his jaw had emerged from the fat of his neck, which had been sloughed away by discipline and ration. Both his eyes were ringed heavily, bruised like wine. His cheekbones were hard and severe. He was almost beautiful.

Still, she felt her body tense at every touch. Her muscles went all cold and rigid. Some part of her resisted him, though she knew there could be no resistance—no hope, even, of delay.

It must have been the first time a girl had been this close to him. He held her too tightly. She said, “What happened to your eye?”

He said, “I wrote you all about it.”

“Can I see?” she said.

He smiled. “Not here.”

She pressed her head against his chest. He ran a hand through her hair. “It’s you I want,” he said. “It’s only you.”

She said, “I know.”

He said, “They tell us, when we’re over there, we can have any girl we want. If only we can make it back.”

She said, “You can.”

He said, “I wanted you even before I saw your pictures.”

She said, “I’m glad.”

“It was you I thought of while I killed them.”

He squeezed her hands in his. He took her to the coat room. They pushed back through parkas and the fleeces, the windbreakers and pullovers, the sweaters and suit jackets. It was warmer and warmer the deeper they went. They were in a nest now, a womb full of overcoats and leather jackets. He pushed her blouse from her shoulder and bent now to kiss it.

“No,” she said. “Wait.” She shrugged him off. “First show me.”

“There’s nothing to see,” he said.

“Show me your eye.”

He nodded, stepped back. Put his fingertips beneath the patch. He said, “Are you sure?”

She said, “Show me already.”

He lifted the eye patch and pulled it off from his head. The wound gaped. It was a dark hole, a secret tunnel. She leaned forward; she touched the rim with her fingers; she touched where it was dry. The world around them went pale. A heat like nothing she had ever felt poured from the empty socket. She leaned forward. It felt like falling, falling toward him, into the socket. Blood dripped from the eye socket’s ceiling, it ran down the walls, and drizzled in faint rivulets from the corner, down the side of his face. Paula pushed past that, and past the membranes, and through the dark. She could see his bright red brain, the molten folds and ridges, roiling in his skull like maggots. She was falling forward and into him.

“How many did you kill for me?” she whispered.

“All of them,” he said.

She was inside his socket now. She was falling inside.