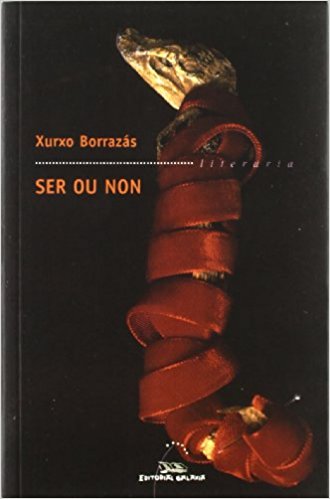

Below are the first three chapters of Xurxo Borrazás’ novel Ser ou non (Galaxia, 2004) translated from the Galician by Jacob Rogers.

1

No one pays a writer any mind. I know it all too well, I’m not demanding blind faith and technically I’m not a writer. I’m just asking for a little attention, maybe four hours. The true stories do the telling themselves. I also know that not everyone enjoys telling a story, what’s pleasing is to listen to one. If we could be characters, literature wouldn’t exist and neither would readers or writers. Putting one’s life at risk is what’s truly intense.

And narrating life isn’t the same as living it, that’s why no one pays a writer any mind.

My name doesn’t matter, seriously. I always speak seriously.

I came to A Pena because they told me there would be no one here, simple as that. There are a thousand places one could go, the vast majority surely more practical and interesting, I suppose that’s why everyone chooses them. Charming places, just a step away. They don’t work for me, period.

I’m alone, the house is large and cars don’t go by.

What you’re reading isn’t the first thing I’ve written. The first paragraphs disappeared beneath a whirlwind of furious ink that soaked through the sheet. It was hard for me to destroy them because the lack of space is spurring me on, paper is becoming scarce, and all that formal experimentation was suicide. I’d better limit myself to explaining what happened as if it hadn’t happened to me, coldly, as if a knife were pressed up against my throat. A writer who feels self-important is like a soul in purgatory, deserving of neither heaven’s glory nor hell’s inferno. Anyone who feels self-important is stupid, whether they’re a writer or not. But anyway, I’m not used to dealing with people, so I might be mistaken about that.

A b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

That’s it, the entire history of literature fits in those twenty-six letters; in seven notes, that of music, in seven colors, that of painting. Literature is action, muscle, tack tack tack, without anabolic-steroid theories, swollen sea foam, or miracle all-purpose silicone. Nowadays any maintenance worker who shows up at the house seems like a Chicago thug, doesn’t matter whether they’re a carpenter or an electrician, a plumber or a plasterer. Within their toolbelt arsenal what always stands out is a silicone gun. At some point they get up off the floor or step down from the ladder and say: I’m going to the car for a minute to get more ammunition, that is, more silicone. It’s the same with writers.

Despite living in the city I’ve always been uncouth, wild, aloof, a lone wolf. Not some heroic figure touched by the solitude of mystics and geniuses, or the pride of a martyr. If anything I’m the lunatic forgotten in a moldy, flaky-walled asylum, or the cross-eyed, slobbery traitor abandoned by his payers and left by the wayside. Not literally, of course, but you get the idea. There’ll be plenty of people who think I’m crazy, but that’s their issue, not mine. In a populated setting, by way of careful study and painstaking restraint, I’m able to talk the talk without attracting any attention and so I get by, or so I think, but that’ll never be my setting. I’m not talking just for the sake of talking. What I feel could be termed “species aversion.”

Now that I’m aware of it, now that I’ve recovered from the gorings and suffocating prejudices of youth, now that I’ve spent more time among people and become more conscious of my own image, more systematic in the analysis of what I feel as well as what I do, now I see myself as a true curmudgeon, without friends or girlfriends, why in hell would I hide it? Would it be better for me to walk around self-satisfied and grotesque like a junky, so mistaken about his appearance that he thinks he’s capable of walking gloriously unnoticed through a playground, a normal guy, when in reality he’s more conspicuous than Marilyn Monroe naked at an assembly of bishops? It never pays to be a junky. I have no relationships because when you have girlfriends and friends you have to talk to them, listen to them cry, make them presents, smell them, forgive them, defend them, step into their shoes, keep them updated. Honestly, I prefer to read. Or knit.

For the record, it’s not my fault. At my First Communion they dressed me as a monk. After mass my mom took me by the hand and we dodged around flashes, princesses, admirals, and groups of family getting together for the festivities. At home she took the rented robe off of me and hung it over the back of an armchair. While she knitted and my grandmother snored with her carrot in hand and her mustache blanketed by crumbs, I sat staring at it for two hours. “Shroud of Turin, O sacred shroud, X-rayed face of Christ,” I prayed.

“There are two kinds of priests,” said mom, “the soccer ones and the ping-pong ones. You got stuck with a ping-pong one, which is also a disgrace.”

I’ve never understood my mother. In the afternoon I continued staring at the starched robe and, hidden among the blinds, I watched the other children jump around and make a ruckus in the street with their new toys. I spit onto the glass and kicked at the baseboard a few times; I’d lost an opportunity there. Mom didn’t notice and sent me to bed, before it’d even gotten dark.

“Do I have to pray?” I asked.

At night I woke up with a fever, put on the robe and went back to sleep folding myself up in it. At that point I still hadn’t learned how to jerk off and recited an Our Father, spoke with God and he said, with some authority, that he’d never abandon me. Childish things. Then he took off like the rest of them.

If all it was were just reading out loud, I’d have an extensive social life. You tell me if there’s anything more beautiful than reading someone a novel at dusk on the beach, some poems in bed or on the grass. Better yet: listening, having someone read to us. Be honest. I’ve never tried but I’m sure of it. It also wasn’t my fault that I never did, seriously

Ever since I was a kid I had enough of everything except for books, books…and now the Internet. But I’m not a “man of my time,” I’m not really sure what that is. Modern technology is a magnificent waste of time and all I salvage from the Internet is its daily usage value, without chic or yuppie “gadgets” or the mythologizing of a postmodern jumping bean. Drawing deep philosophical conclusions about the connection of some cables is something I consider utterly excessive. I’m not contradicting myself if I say that the condition I put forth for renting the house was a phone that made internet connection possible, via satellite, or however: the price and speed made no difference to me. I wanted everything to be plain and empty, just the world and myself, but no landscape hides as many surprises as a desert, or a village.

2

The tiny hamlet of A Pena, at the edge of Galicia, Asturias and León, comprises two dozen structures on the hillsides of a boulder-capped mountain. “I’ll fall any day now,” the rock threatens. “When its least expected I’ll slip, and whoosh, go fuck yourselves!” The houses are thrown together one on top of another and, except for mine, they’re ivy-covered ruins arranged irregularly in two imperfect concentric circles, perhaps a badly done spiral, in the vein of a defensive fort. At one point it must’ve been, and looked at from afar the village retains a certain appearance of warding off enemies, or at least being suspicious of outsiders. Nowadays I’m the only inhabitant and it’s captivating to imagine that along these streets and alleys hundreds of people used to circulate daily: life was teeming with large families, there were children prancing about—red faces and chubby bodies, tanned hands and toothless mouths—couples hurriedly making love in the shrubs, ox-drawn carts loaded with mowed grass, fresh cow dung fuming, bagpipes and tambourines livening up the long summer evenings. It’s captivating because now all of that has disappeared.

The man who rented me the home is probably trying to buy the whole village from the emigres in Barcelona. His parents were from here, and more than for profit, he does it out of a kind of Cainism or oedipal compensation. According to the man himself, with what I pay him for a month he already has enough to buy an Asturias-style granary of good-quality, and a certain Liberto’s pigpen to boot. This Liberto is a taxi-driver in Esplugues de Llobregat; he married an Extremaduran and built a villa in the Montseny Mountains. “For him, getting rid of a pigpen in the village is like clearing his memory, brightening up the past, and making some money on top of that,” according to my landlord.

He sees himself as the emigrant who got rich in South America and came back to build a school, but at this rate it’ll all shortly be his: he’ll have to think about what to do afterwards. Maybe even restore it with public subsidies and fill it up with tourists dressed like soldiers driving SUVs, bringing rifles with them to hunt country deer or pregnant boars. They’ll thunder through the amphitheater of the valleys and sow the creeks and passageways with lead, poisoning mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and other birds while they’re passing through. If this were to happen I’d never return. It’s a figure of speech, I probably won’t ever come back, whether they build a Buddhist temple or a casino, a zoo, a brothel, or an arms factory. If on my way to another place I might have to go through A Pena, I’d make a long roundabout in order to avoid it, not for any particular reason, I just know that’s what I’d do. When you’re done reading these pages you’ll understand me better, you’d do the same. Just listen for now. I’m trusting that you won’t repeat this to anyone afterwards.

I love the Internet for the pornography; the rest of it’s only good for those who like the fuckery of cheap ostentation or pretending to be hip, the bullshit of the idle. The things that interest me are very few, I’m not fond of word games or ambiguities which drive me to worthless interpretations, to abstract assessments, and I like wasting time even less, such as with romanticism or eroticism. I warned you, I’m a real curmudgeon. As long as I don’t get into anyone else’s business I don’t have to give explanations anyway—holy shit!—and it’s clear to me that there are worse people out there. I’m like Nietzsche, a vitalist with a grey life.

One night I went to an X-rated theater downtown and had to buy my ticket, clean my seat, smell the stale semen for an hour and half, be unable to get up or smoke, listen to donkey moans in every corner of the room, step on streams of spit or something more viscous, and be the object of more than one romantic, erotic, sarcastic, and undesired proposition. Upon departing from that hell, before the lights of the theater came on, I must’ve withstood a barrage of kisses and at least one green loogie launched in the dark which hit me right in the ear, and which I had to clean off with the bottom of my shirt. Outside the buses had stopped running and I had to pay for a cab to get back home. Never again. I’d even chosen a weekday and the movie was in German, without subtitles. It must be like death on the weekends.

Either I was oversensitive that fateful night or at least I thought I could hear how my cab driver sniffed to the left and right, seeming to imply: “What the hell is that smell? How do you have the nerve to get into my cab like that? What, do you want to ruin my job, you asshole? Do you think this impeccable public service is the bathroom at a whorehouse, or what? You, of course, since you don’t have any mouths to feed. What the fuck do you have!” It was taxi 419 and any of his cab-driving colleagues would’ve done the same, I don’t blame him. It just surprised me that he could detect the smell of semen like police dogs can with cocaine.

“Carballo, hey, where are you Carballo?” They were calling him over the radio taxi.

“Coming up on As Travesas,” he answered.

“Could ya pick up a girl at Toys’R’Us?”

“Hooker?”

“I guess.”

“Negative, bud,” declined the cab driver. “I’ve had enough for tonight.”

It’s been three years now and every time I see a cab I lower my head, look at the number, and my heart leaps out of my chest.

That night, I grabbed a bottle of soda water as soon as I got home and swallowed most of it in one gulp. In critical situations, in order to escape alcohol, I abuse carbonated drinks. I fill myself with bubbles until my eyes inflame and tear up. Soda water makes my ass burn instantaneously and without fail, so I already knew what was in store for me. I did it for exactly that reason, more than a half liter. I could feel the sugar penetrating into the fissures of my gums and burped three times. I drank the rest of the bottle and spit into the sink. The drink had shot up my nose and I shook my head to the left and right. The burning came within the matter of a minute. I washed myself in the bidet with warm water and took one of Mom’s anti-inflammatories. It was my way of punishing myself, my path to sainthood: soda water.

Luckily, and thanks in part to computers, fetishisms aside, I’m done with those pointless rovings, which doesn’t mean I’ve gotten them out of my mind. Looked at from a different angle, that night in the theater was a pity. The movie was really good, I mean…the women, these things only look proper on the big screen, there’s no comparison. In the flick, like almost every one in the genre, there was an excess of blowjobs and half-hard cocks. This type of film appeals to whom it appeals, there’s no need for us to pretend. The actors themselves say they don’t feel anything, that they do their job and that’s it. It’s not nothing and that’s not it! If they don’t get turned on, how the hell am I going to get turned on? Who are they trying to con? How could they hold a curvy, butt-naked woman in their hands like someone who mechanically stamps packages at the post office? And what about the women? It wouldn’t surprise me if they were playing the same game and hiding it better, but I forgive them for it. I’ve even heard that when some painters are copying from a photo they place the model upside-down, that way the reality depicted doesn’t prevent them from concentrating on the lines and colors. And what about the human factor? Huh? Well now it looks like I’m going to have an attack of sentimentality. Me, of all people! If I were a pornographer, I’d make movies where the take was repeated until the coming was authentic and there were no cocks or men to be seen. I’d compensate for the extra expense on film by saving on actors. Going back to the movie from that night, and in spite of everything, I recognize that sex in German gets me horny, and an erect nipple in close-up, of which there are plenty, becomes a volcano.

3

My background in science is no obstacle to my love for literature, although for some kinds of literature it is. And yet what could be more poetic than the story of the great discoveries in physics, or more scientific than the best literature, that of encyclopedias.

I love books like I love myself. They’re fleeting loves because I rarely buy or possess them. If I had money, I would. Maybe now. The length of our relationship lasts equally as long as the time spent voraciously reading or that of the library borrowing period. Then we bid each other farewell like two lovers who lost consciousness during the night and committed every kind of excess but at dawn get dressed in silence and go their separate ways without asking for numbers or trying to convince themselves that what happened could’ve simply been a dream.

In the library there are basically just students going over notes and elderly people reading one newspaper after another, hiding the ABC behind O Faro so that no one deprives them of another dozen drab columns. The librarians themselves—a woman of around fifty years old with an imitation pearl necklace, and a dark-skinned boy with hair gel and Ralph Lauren polos—look me over from head to toes every time I check out a book. With the old people they permit everything and yet they censor me with a disdainful superiority, as if I weren’t going to return the borrowed book and they wanted to have a description ready for the police archives. They look at me as if I were picking up the weekly copy of my subscription to a pedophilia magazine.

Sometimes they try to scare me off with successive repetitions of “it’s checked out.” I obstinately seethe at the catalog and choose another title, a classic second-rate philosopher, the history of our provincial government by way of its presidents, the biography of an obscure soldier. People whine about poor reading habits but then we go and treat someone who reads like they’re a monster. Society carries the contradiction within itself: put-together at the face and unraveled at the ass. Some libraries are the ass.

This outright disdain, these setbacks that books and I find ourselves forced to overcome in order to arrange our semi-clandestine meetings, only make our love grow stronger. They display their affection just as much as I do, and as a result, on top of reading them I’ve also written one, for the moment. I sent the novel to Barcelona, for the prize, to torment myself within defeat, within the sulfuric contempt of the pundits and the sweet death of public indifference. It turned out that I won, an unknown debutante in a commercial macro-competition known for being rigged and a text of just one-hundred and seventy pages. Shouting to the world what one writes, being heard, is equivalent to opening Pandora’s Box. In moments of sleepiness and idealism we picture the Ark of the Covenant, but in the end it turns out to be that same old can of worms, make no mistake.

The verdict resulted in a bombshell from which I’m not even somewhat recovered. Sometimes I think I am but it’s precisely the lightheadedness derived from success that makes me think so. I came here to get over the shock and supposedly to write another novel. What I really wanted was to win more prizes, to receive a phone call that would make me tremble, and to believe that all my repressed sadistic impulses could finally enjoy their objective correlative. The experiences between pleasure and pain are the truly pleasurable ones, and we all like to repeat them. Hush, hush, I don’t want to put you on the spot, you don’t have to say a single word.

I also came to escape from the Galician nationalists who decry me for writing in Spanish. I always speak Galician because I don’t speak much at home, but the language should disappear just as much as I should. When one takes an interest in extinct species one becomes familiar with the beauty contained in knowing oneself to be endangered, a lynx, an eagle, a gigantic blue whale, or a miniscule invertebrate at the mercy of imperceptible variations in climate or imbalances in the food chain. To be one of the last would fill our lives with meaning. That’s why I speak in Galician and don’t write in it, because of the smell of latent extinction. I’ll write in it one day when we’re fewer. If you’re wondering why what you’re reading is in Galician, it’s because it’s not writing, it’s merely speech. Any outside hand on these pages would act as an explosive laboratory catalyst, would turn them into a posthumous work.

Those who keep piling up adjectives in order to condemn my choice of language are wasting their time, and they disappointed me by responding to my provocation talking like politicians instead of insulting and threatening me. They, with their historical allegories, their moral misery disguised as nostalgia, and their eternal urban-rural conflict. Good manners and hypocrisy are enemies of intelligence, and a good index by which to certify societal paralysis. I call you all idiots and you respond with an academic paper. Sucks for y’all.

I also came to get lost in this middle of nowhere to free myself from the press which ever since reading my novel has hailed me for the “courage” not to write in Galician. And might that not have something to do with the bestowal of the prize, even just a bit? A newspaper with a huge readership has already offered me a weekly spot on their last page; it’d be impossible for me to do it worse than others, a column that’s well-paid and without any preconditions. Doric, Ionic or Corinthian: the artist chooses the style, joked the guy from the paper.

It’s all settled. I would write about bars, “the question of gender on bathroom doors,” a new place every day. Men with frock-coats and top hats, or maybe canes, women with parasols and belle époque dresses. That’s what was masculine and feminine. The mustache of a French worker at the end of the 19th century and a pair of sensual lips. A blazer and “cigarette” pants along with Mary Quant’s miniskirt. A mannekin-pis with his parabolic squirt and a baby girl with blonde braids and a straw hat. I had neither top hat nor mustache nor “cigarette” pants, nor did I urinate in fountains. My thing was literature, letters: H. M. There it is: homes e mulleres. Men and women. And, out of all the letters in the alphabet, the masculine is symbolized by the most arbitrary, H, the one that’s mute, empty, which existed as a whim or as a basis for illegitimate authority, an injustice. I had a list of bars made up and that series would give me something to blabber about in my newspaper column for a few months, until the readers got tired of my bathrooms and flushed them down the toilet. You can’t make everyone happy, it’s good enough for someone to accept us even if we ourselves hate them.

Newspapers don’t come to A Pena, and literary disputes as well as nuclear tests seem like useless chitchat or nonsense, byzantine theological debates. Nevertheless, at the end of this month everything’s going to get tangled up again: news, family, routine, my recently released public persona.

Alongside the reactions of surprise at the winner’s identity—for many a symptom of the contest’s well-known rottenness, and therefore of the much desired decline of the huge publisher—illustrious pen names appeared unmasked in the national newspapers, names that had participated in the contest by taking old projects out of the closet, reviving them, and dressing up their unnamed cadavers, directly encouraged by the very publisher which now ignored them all because of some nobody. A bitter and melodramatic controversy took hold, and even some of the judges who didn’t vote in my favor got involved. I didn’t intervene—what was I going to say?—and my silence was interpreted a million different ways: taciturn, wise, mysterious, fraudulent, Galician. That’s the power silence has.

I ultimately came to the village because of the issue with the critters, ashamed of myself. Maybe that was the only reason, the definitive one. One can’t get rid of oneself very easily, but the mirrors can always be turned around. What’s most similar to this is to flee, because to flee is always to flee from mirrors. Shame is especially associated with the landscapes which engender it.

Although unwittingly, I also came to settle accounts, to get what I deserved. And boy did I get it

In my thinking literature simply constitutes a way of delaying pain, a sedative for the disheartened. At one point I saw it as a drug and then I started to hate it like a medicine: its function was prophylactic and I, bitterly disappointed. Now I see it as a medicine I can’t go without. I remind myself that I have to obey the doctor, that it’s an obligation, but I know it’s become an addiction. As a child I faked colds and headaches so that Mom would give me a spoonful of codeine. It might not have been a drug, but it was more than a medicine: just smelling it, I became entranced. It’s the same with writing.

I know I have no literary talent at all, I was neither born for it nor will I die an artist. I have no idea, fucking hell. Between the media uproar, the applauding, and shaking of hands I was out of it for a few days, but the nervous frigidity of my personality knew how to negotiate that downpour. In the novel I wrote, actually a series of stories I linked in order to present them for the prize, I limit myself to narrating some bits badly chosen and pulled from my grotesque, undesirable toerag’s life. I did it all wrong. I thought people wanted heroes and happy stories but in this world there’s more shit than some of us smell, and that’s good for me. The recycling of failures is constantly more complex, more useless. The boundaries constantly have to be moved because there’s just more trash and failure. Some people aspire to this mortal heaven and meanwhile it doesn’t come they vomit on the street corners. I’m waiting for that moment leaning back with a bunch of grapes in hand. For me writing a happy and made-up story would be as pointless as writing about the legends of Samoa or the applied mathematics of interplanetary rocket propulsion. On the other hand, the macabre and the pathetic go a long way when there’s a thick barrier of protection between them and us, whether it’s the barrier of the pages of a book, the barrier of language, of the rules of a story, or all of them together. For some members of the jury—based on the aforementioned controversy I deduce that they’re the ones closest to the organizing publisher—even the stereotypical settings within this land of fog, witches, lunatics, enigmas, and apparitions, should’ve been held as a layer of protection and mystery. Outside of that string of topics I don’t know what commercial value they could’ve seen in me, maybe that of the Entroido Carnival’s king?

They spoke of Torrente Ballester and Camilo Jose Cela, of Cunqueiro and Fernández Flórez, of Valle-Inclán, of “magical and parallel worlds, of a language rooted in the earth, of the multi-faceted structure, of the breakdown of the barriers between fiction and reality with a personal aesthetic which overcame the vacuity of postmodern hybridizations.” I didn’t understand it and as such I said nothing. I also heard the dialogue was very realistic—what realism and what a load of shit, if I don’t have a dialogue with a single fucking person! I’ll say it again: what I narrate there is my life, as long as I don’t have another, I’m not sure what the hell else I could tell. Make up another story? Just like that, out of nothing? That would be absurd. In order to write something original, one should first invent their own language, a new and exclusive language. The rest are combinations, commercial transactions, word games repeated a thousand times. I don’t have my own language and I’m not original. I didn’t even suffer a childhood which could be considered miserable and upon which I could lean, unlike the majority of true artists. I simply feel that I lacked a childhood, which is impossible, obviously. What does that mean, anyway?

“He’s a strange guy,” said the literary critic. “But on the other hand…”

“You should all vote how you want,” placated the representative from Editorial Universo. “The company trusted you to make a thoughtful decision. In fact there you have it, the little novel made it through the filter. For us the easiest thing would’ve been to block its path early on, then there would’ve been no issue.”

Last year’s winner leaned forward in her chair and rested her elbows on the table:

“I think what needs to be done is to compare it with the rest. The other nine are proper novels, and there are three that I like quite a bit. I had a good time reading them and went on with my life. I can’t say the same about this one, I didn’t exactly “have a good time,” but it’s definitely the one that left me least indifferent. It’s ironic, literarily as well as…I’m not sure.”

“The guy’s invented a fiction in order to conquer reality, it’s the spirit of an alchemist. Haven’t you all asked yourselves if this novel didn’t exist previously?” commented the university professor, “if it’d been presented for the prize some years ago without winning, and now he wants to take his revenge within fiction?”

“All this metaliterary bullshit,” interrupted the veteran writer, the man of the house, “fucks with me a little bit, sorry, honey.” He gestured towards the lady who’d won the year before. “I’ve been on this jury for seventeen years and there’s always some pipsqueak who wants to give me lessons about literature. They should write a novel like yours, goddamnit, with its story, a careful use of language, and above all characters one can empathize with, not this repulsive pest…how did he himself say it? A toerag. The discussions are unnecessary with a good novel, aren’t they? It validates itself and that’s that. Last year the decision was firm before we’d even finished our coffee; I’m not saying it to flatter you, sweetheart.” He turned towards the professor and asked: “that’s the right word, isn’t it, metaliterary?”

“We at the firm don’t want you all to feel like there are conditions. Each year the jury is different and hearing each authoritative opinion will only increase the prize’s grandeur. You’re well aware of our publishing tendencies and we’re hardly going to decide on a winner at this stage. I’m seeing that there’s some confusion; how about you all take a break and continue after lunchtime—at the restaurant, as you know, you can have whatever suits you, for food and drink. If we have to get you all together nine times, we’ll do it. By the way, none of you said anything about the fountain pen: in my view where there is gold all other metals are irrelevant.”

“A gem,” interjected the university professor. “I barely know how to use a pen anymore, not to mention a fountain pen, but it’s undeniably a gem.”