Why So Serious? How Mental Illness Became Laughable

Sarah Hagaman, 2024-25 RPW Center Graduate Student Fellow. This year’s group is exploring the theme of Emerging Technologies in Human Context: Past, Present, and Future

Can you laugh at jokes about mental illness—even a joke about suicide? Breakout standup comedian Taylor Tomlinson thinks so. Yet nervous audience laughter—the equivalent of a collective tee-hee or a self-conscious giggle—arose when she joked about her recent bipolar diagnosis in her 2022 special, “Look at You.” Tomlinson noticed the response, saying, “If you’re not laughing, congrats on your serotonin. And if you’re like, ‘What’s serotonin?’ Don’t worry, you have enough.” Later, she admonishes the tittering crowd about their response to her dead mom jokes: “I’m here to tell you that if you’re trying to be a good person at a comedy show, you’re wasting your goddamn time.” The set ends with bits about fickle suicide hotlines and masturbation. By this time, the audience was roaring.

Women have historically been the butts of jokes. Kitchen-themed woman jokes abound, as does that stereotype that women simply cannot be funny, a point argued in the infamous 2007 Vanity Fair essay titled “Why Women Aren’t Funny.” Despite the bad press, women have since entered professional comedy in droves, creating what Kirsten Leng calls the “golden age of feminist comedy.” Mental illness has become a widely discussed topic in much feminist standup: Tomlinson’s discussions about bipolar joins Maria Bamford’s revelations about her obsessive-compulsive disorder; and Aparna Nancherla, Sarah Silverman, Rebecca O’Neal, and Cristela Alonzo reflections on living with depression and anxiety.

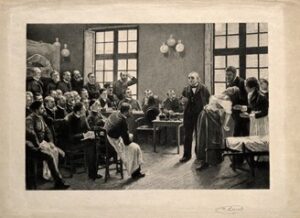

For women, mental illness has not always been comedic gold. Hysteria was a gendered nerve disorder in the nineteenth century theorized by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who cited fits of laughter as a symptom of nervous disease. The second volume of Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière, which contains photographs of Charcot’s patients, describes a woman “who had her period, was quite frightened. She was struck with a fit of laughter and, after a few minutes, with hystero-epileptic attacks.”(1) Uncontrollable laughter indicated hysteria as a clinical condition—and almost all hysterics were women.

In connecting with her audience, Tomlinson creates a shared hysterical sensation: laughter. The resulting affective charge bonds the audience into a group experience, one that I call “reclaimed hysteria.” Reclaimed hysteria is a collective laughter that mimics a symptom that historically rendered mentally ill women into pathologized objects. Although not all audience members can relate to this condition, they are invited into the collective hysterical experience. Unlike historical iterations of mental illness, Tomlinson and other feminist comedians create a community that reclaims the terms of hysterical laughter.

Women performing standup with mental illnesses become both the subject and object of their comedy in ultimately liberatory ways. It’s crowd work with collectively therapeutic potential.

(1) Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière, vol. II, 189.

Sarah Hagaman is a fifth-year PhD candidate in the English Department. She specializes in post-1945 feminist literature, and her research and teaching interests include 20th– and 21st-century portrayals of mental illness, psychiatry, and mad aesthetics. Her dissertation, The (Post)confessional Mode, traces the feminist literary reception of psychiatry in the late twentieth century, intertwining global psychiatric histories with experimental fiction, memoirs, television shows, and standup comedy. When assembling these works together, she proposes that an irreverent, parodic form of self-expression—or what she terms the postconfessional mode—emerges. Her research appears in Medical Humanities—BMJ, Literature and Medicine (forthcoming), Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, and ASAP/J.

Sarah Hagaman is a fifth-year PhD candidate in the English Department. She specializes in post-1945 feminist literature, and her research and teaching interests include 20th– and 21st-century portrayals of mental illness, psychiatry, and mad aesthetics. Her dissertation, The (Post)confessional Mode, traces the feminist literary reception of psychiatry in the late twentieth century, intertwining global psychiatric histories with experimental fiction, memoirs, television shows, and standup comedy. When assembling these works together, she proposes that an irreverent, parodic form of self-expression—or what she terms the postconfessional mode—emerges. Her research appears in Medical Humanities—BMJ, Literature and Medicine (forthcoming), Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, and ASAP/J.