A History of the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities

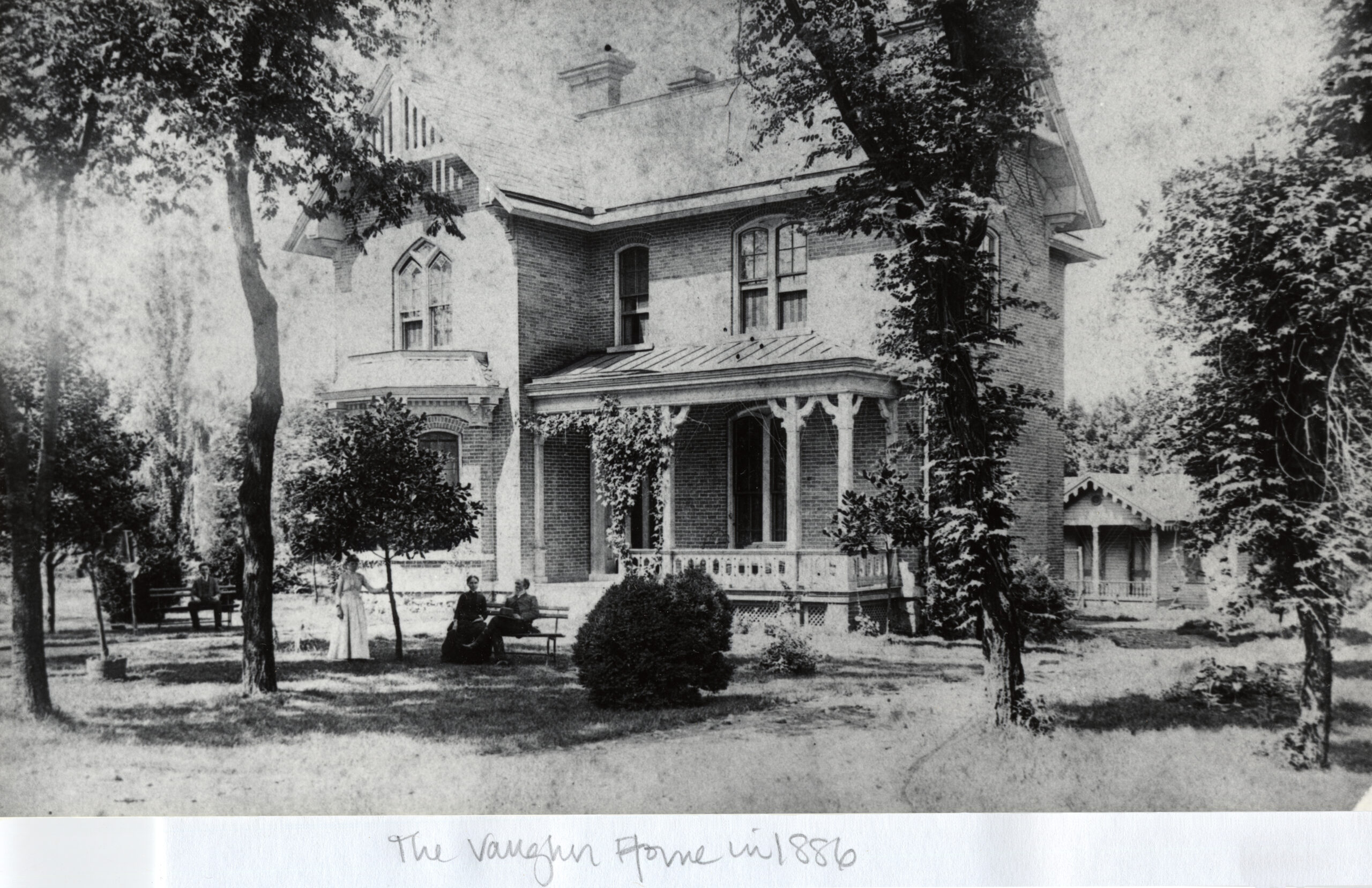

In the fall of 1987, the Vanderbilt University Board of Trust voted to name one of the university’s seven original faculty houses the “Vaughn Home” in recognition of the important contributions made by the Vaughn family to the university. This was a fitting tribute to a family whose influence at the university spanned three generations. The building has served as a residence for married faculty, a dormitory for men and for women, and offices for the Departments of Romance Languages and teaching assistants in Western Civilization. It presently houses the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities.

Residence Five

From 1884 to 1912, Residence Five, as it was commonly known, was the home of Professor and Mrs. William J. Vaughn. Since the University’s founding in 1875, Chancellor Landon C. Garland had been attempting to recruit William J. Vaughn to fill the Mathematics chair, one of eleven chairs in the “Academic Department,” now the College of Arts and Science. In 1882, Vaughn accepted Garland’s offer and left the University of Alabama to join the Vanderbilt faculty with an annual salary of $2,500 and the promise of a rent-free house on campus. The crescent of homes at the heart of the campus was the site of much lively activity, as faculty members raised their children in the midst of the college. The Vaughns raised their five children—Eugene, Robert, Will, Harry, and Stella—in the faculty residence. Stella Vaughn addressed the Vanderbilt Woman’s Club in 1925, recalling her early days as a child on the campus:

In those days the campus was simply alive with children, a condition quite different from that of the present time.

For thirty years the latch string hung on the outside of our door, whose portals swung wide to faculty and students alike. When I was a little child, Bishop McTyeire used to take me by the hand and walk along the paths telling me the names of many of the trees whose growth he watched with keen interest. The bishop was very fond of children and whenever a snow fell, he would get out his one-horse sleigh and drive from house to house picking up the little folks, and all that couldn’t get in the sleigh hung their sleds on behind for his horse to pull.

William J. Vaughn served as professor of Mathematics for 30 years, professor of Mathematics and Astronomy for 16 years, and University Librarian for 26 years. He is reported by many to have been a true polymath; a mathematician by training, he could read at least a dozen languages, including Sanskrit and Russian. His knowledge of history was highly regarded; his book collection of 6,000 volumes included 500 volumes in Napoleonic studies. James H. Kirkland, who became Chancellor of the University in 1893, often told a story of a trip he made to Leipzig. While there, he called upon a famous international bookseller. When the proprietor learned that Kirkland was Chancellor of Vanderbilt, he commented that he was in regular correspondence with a member of the faculty by the name of William Vaughn. Chancellor Kirkland liked to recount this episode as an example of the professor’s widespread reputation as a knowledgeable book collector. Professor Vaughn was also an active participant in the establishment of a chapter of Phi Beta Kappa on the campus in 1901, a tribute to the growing successes of the young university.

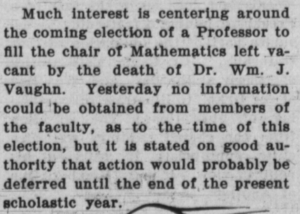

On December 17, 1912, Professor Vaughn died at age 79 in Residence Five. His health had been failing during the fall term, and when he felt his death was imminent, he called for Chancellor Kirkland to come and meet with him. He instructed Kirkland, “Tell the boys for me that this is not a sad occasion, that I got more than was coming to me and have received more than was my share of the good things of life—that my classes have shared with me their youth and that perhaps they gave to me more than they received.” The Vanderbilt Hustler (the student newspaper) reported his death, stating “The grand old man of Vanderbilt is gone.” Professor Vaughn left his library collection to the University; a portion of the Board of Trust minutes from June 1913 reads:

The William J. Vaughn Memorial Library is the most valuable collection of books ever received by the University as a gift. It consists of about 6,000 volumes. In the Department of Mathematics, it is of course, preeminent, but it is of almost equal value in the fields of history and general literature…. It is with great satisfaction and gratitude that record is made of this gift characteristic in every way of the donor and a worthy memorial of his long and useful life.

At the Annual Alumni Dinner held in Kissam Hall 11 June, 1923, a group of alumni presented to the university a portrait of William J. Vaughn. The presentation was made by Dr. W. H. Witt (BA 1887, MA 1888, MD 1894), who said, “We feel that there should be something within the walls of Vanderbilt University, something tangible, something that will remind the present and coming generations of the great work of this man… He gave his best to those who met him in his own library—occasions which gave a glimpse of his profundity of learning and his uncanny knowledge of books.”

Ironically, the same issue of the Vanderbilt Alumnus (April-June 1923) that reported the presentation of the portrait of William J. Vaughn also contained a brief report which carried the headline “Grandson of Dr. Vaughn Wins Highest Honors.” In 1923, graduating senior Williams S. Vaughn achieved the noteworthy record of being the first student to graduate from the university having earned all A’s during his four years of study.

William J. Vaughn’s death did not end the family’s active influence at the university. Most notable are the contributions made by his daughter, Stella Scott Vaughn (BA 1896) and his grandson, William S. Vaughn (BA 1923).

MIss stella

Stella Scott Vaughn was a trailblazer for equal educational opportunities for women. Born November 4, 1871, Miss Stella (as she was affectionately known) came to live on the Vanderbilt campus with her family at the age of 10 and remained unfailingly loyal to, although sometimes critical of, the institution for the rest of her life. She received her early schooling with the other faculty children in a one-room school on the western edge of the campus.

Entering Vanderbilt as a first-year student in 1892, Stella Vaughn was one of 10 women students in the Academic Department. Beginning with the 1892-93 year, women were “admitted by courtesy” to classes offered by the Academic Department. Although the women who were enrolled during this period were not allowed to matriculate, they could complete any of the degree programs offered and were subject to the same rules as their male counterparts. During Miss Stella’s student days important changes regarding the status of women were underway. In 1894, the faculty voted 7 to 6 to allow women to compete for university prizes and awards. In 1895, a new record was set when three women graduated in one year. The year following Miss Stella’s graduation, the faculty voted to allow women the opportunity for formal matriculation. The women did not, however, have access to dormitories and lived in university-approved boarding houses near the campus.

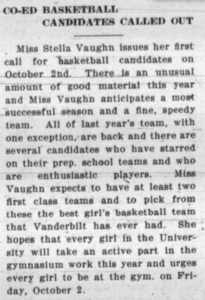

After her graduation in 1896, Miss Stella remained on the campus as the women’s physical education instructor, becoming Vanderbilt’s first female instructor. In the fall of 1896, Stella Vaughn organized Vanderbilt’s first women’s basketball team and served as team captain. Samuel Anderson Weakley (E 1911), a member of the men’s basketball teams of 1909 and 1910, wrote an account of the women’s first game March 13, 1897, in the Vanderbilt gym against the Ward’s Seminary women’s team. “The Vanderbilt team won by a score of 5 to 0 (a field goal counted five points in a girls’ game then). The game had gone 0 to 0 until just before the end, when Stella Vaughn threw a long pass to Elizabeth Buttorff near her goal and she in turn made a desperation throw at the goal.” Weakley goes on to state that Stella Vaughn should be “queen to reign hence forth” as Vanderbilt’s “Miss Basketball.” Another report appeared in the Vanderbilt Hustler. Although male students were not allowed in the gym to watch the game (doors and windows were blocked), a reporter admitted to having hidden in the gym before the game. “The agility of some of them was really surprising,” wrote the Hustler spy, “as they got around after the ball in a manner that would put some of our gym graduates to shame.”

Stella Vaughn served as the women’s physical education instructor and basketball coach without pay for nine years. In 1905, Chancellor Kirkland proposed that Miss Stella receive an annual salary of $100 for her work with the female students. Eight years later (shortly after the death of her father), the Board of Trust voted to increase her salary to $200 per year. At the meeting of June 16, 1913, Chancellor Kirkland stated:

I recommend that Miss Stella Vaughn be given $200 instead of $100 for her work with the young ladies. It is of great value to the young women studying at the university, and she has not measured her services by the time demanded of her according to her contract. She has not only taught them in the gymnasium, but has supervised their sports and in a general way has acted as advisor and friend.

Miss Stella’s accomplishments and those of her “girls” came not without struggle. As women garnered more academic honors during the early 1900s, questions about women’s proper role on the campus arose. In 1914, the women outpaced the men with an academic average of 81.72 percent compared to the men’s 71.47 percent. Women won the Founder’s Medal in the Academic Department each year from 1908 through 1912. Chancellor Kirk land continued to believe that coeducation was harmful to the institution, and hoped for a separate educational facility for women. “The girls at Vanderbilt have worked against the odds,” wrote Miss Stella at about this time, “but they are a ‘plucky bunch’ and not easily discouraged. They have slowly but surely won a place for themselves by their perseverance.”

In May 1915, a faculty committee led by English professor Edwin Mims examined a host of issues affecting the women students. The committee was favorably disposed toward the women, and Mims recommended appointing a Dean of Women and establishing a social center for the female students. However, at the urging of Mims, the committee also recommended the termination of all women’s intercollegiate athletics. Intramural sports and physical education were laudable, the committee wrote, but women’s competitive athletic contests were not in keeping with the “best tradition and practice of the entire country.” The faculty tabled this recommendation and Miss Stella’s teams continued to compete against other colleges.

At the Board of Trust meeting in June 1915, the Trustees considered the Mims committee’s recommendation to hire an official Dean of Women (Miss Stella was long considered the “unofficial Dean of Women”), although they took no action on the matter. However, the Board did appoint an advisory committee for the women. The job of the committee, whose membership included Stella Vaughn, was to “assume a general attitude of ad visors toward the young women, particularly the Freshmen, and also maintain a certain general oversight over the social life of all the women students.”

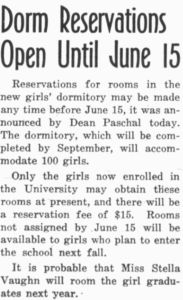

In addition to her role as physical education instructor, Stella Vaughn’s home on Highland Avenue was one of the approved boarding houses for the female students. For more than thirty years, Vanderbilt boarders were a part of her home. When the university hired a Dean of Women in 1925, it was due to the work of the Alumnae Council. Formed in 1923, the Council sought certification from the American Association of University Women (AAUW). In order to certify a chapter, the AAUW required that a campus meet three standards: a Dean of Women, a women’s dormitory, and physical education facilities for women. Chancellor Kirkland refused to spend any of the university’s endowment earnings for these objectives but told the Alumnae Council if they could raise the money, he would work with them. The women set about fundraising through various sales, gala presentations, and individual donations. In 1925, they were able to pay $3,000 a year for a Dean of Women. In the same year, in his address marking the semi-centennial of the university, Kirkland reiterated his position that Vanderbilt was founded as an institution for men and that “its general tone and atmosphere is that of a college for men and will probably so remain.”

In 1926, Stella Vaughn spoke to the Vanderbilt Women’s Club about the university’s first fifty years. She spoke about her colorful childhood memories on the campus, and the many people who had contributed to university life, from Bowling Fitzgerald, porter of the Kissam dormitory and football trainer, to the first Chancellor, Landon C. Garland. In this address, she praised the university for its recent hiring of a Dean of Women but went on to talk about a campus tour of the future:

In closing I want in imagination to take one more trip with you around the campus. In place of the old gymnasium there will be a commodious building with all conveniences and with swimming pools for both the girls and boys; and we observe a girls’ dormitory, the removal of the professors’ houses, additional science buildings, the second unit of the Hospital, and in place of the old Science Hall and residence in the rear, a magnificent library to which all roads will lead.

Miss Stella was a founding member of the Kappa Alpha Theta Sorority. Originally established on campus as the Phi Kappa Upsilon, the local independent sorority became a branch of Kappa Alpha Theta in 1904, the first in the South. Stella Vaughn became the first initiated member of a national women’s fraternity at Vanderbilt. She gave the group a small lodge next to her home on Highland Avenue to use for meetings and other social functions. Miss Stella served as adviser to the chapter for more than fifty years; until her death in 1960, she gave the annual orientation talk to the sorority’s new members.

In 1958, Stella and her brother Harry Vaughn (DDS 1894) presented twenty-six volumes of clipping books to the Joint university Libraries. The scrapbooks which the two had compiled over the years contain newspaper clippings about the university and include a record of the university since its founding.

Stella Vaughn died in October 1960; a few weeks short of her eighty-ninth birthday; Vanderbilt University had been at the center of her interests for seventy-eight years. Once asked about her relationship to the university, she replied, “This campus life is a very great privilege. It’s the life of me.” The Nashville Banner reported, “Miss Stella Scott Vaughn, the grand old lady of Vanderbilt University, is gone.” In 1963, the university named one of the four new women’s dormitories in the Margaret and Harvie Branscomb Quadrangle the Stella Vaughn House.

new generations

Like his father Harry and his Aunt Stella, William Scott Vaughn spent much of his child hood on the Vanderbilt campus. His father graduated from the Vanderbilt School of Dentistry in 1894 and practiced dentistry in Kansas City, Missouri, where William Scott Vaughn was born December 8, 1902. When Bill Vaughn was four, his family moved back to Nashville; his father left the practice of dentistry (a doctor advised him to “get out of his office” for health reasons) and went into the contracting business. Harry Vaughn is remembered by many as an ornithologist and bird-egg collector; Bill was said to be the best tree climber on the Vanderbilt campus as a result of his father’s interests. Dr. Vaughn was a founder of the Nashville Children’s Museum, now the Cumberland Science Museum. When he retired from the contracting business in 1944, he said, “I’m too old to begin another career, but I’ve got time to start a museum.” He donated his bird egg collection, one of the most complete in the South at the time.

Upon their return to Nashville in 1906, the family lived in a house on 24th Avenue, just behind the campus home of William J. Vaughn. Bill Vaughn often spoke of this time in his life, when his grandparents’ campus home was a second home to him, and his Aunt Stella was a second mother. He said that between the ages of five and ten, “I inhaled Vanderbilt with every breath I took.” Women students boarded in both his parents’ and grandparents’ homes, and he heard about university life every evening at dinner. He must have heard a great deal about Aunt Stella’s basketball games!

In 1912, Bill and his brothers Charles and Houghton moved with their parents to a farm in nearby Brentwood; their new house did not have electricity, central heating, or running water. He attended Robertson Academy where he was a star student; he skipped the eighth grade and enrolled at Nashville’s Hume-Fogg High School.

In the fall of 1919, Bill Vaughn entered Vanderbilt. He won the mathematics prize in his freshman year, the first of many accolades he received as a student. A German major and English minor, Bill Vaughn graduated from Vanderbilt in 1923 with a record of all “A’s.” He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, was awarded the Founder’s Medal, and was named Class Poet. After graduation, he attended Rice Institute where he completed an MA in mathematics in 1925. He then attended Christ Church College, Oxford University, as a Rhodes Scholar and received a BA honors degree in mathematics.

In the spring of Bill Vaughn’s senior year at Vanderbilt, Professor George Pullen Jackson suggested that Bill Vaughn, who was his “best student in German,” tutor Miss Elizabeth Harper. She was preparing to enter the Royal Conservatory of Music in Leipzig, and needed to be familiar with German. Elizabeth and Bill stayed in touch during her four years of organ and piano study at Leipzig and married in 1928 in Rochester, New York, where Bill had begun work as a mathematician and physicist in the Development Department at Eastman Kodak. Throughout his lifetime, Bill Vaughn retained his interest in Vanderbilt. In 1952, he was elected to the Board of Trust. He served on the Board for a total of forty-three years and was Board President 1968-1975. The years of Bill Vaughn’s service on the Vanderbilt Board of Trust were years of great change for the university. The size of the university’s endowment grew significantly; new classrooms, laboratories, and dorms were constructed; the university added several new schools and doubled its enrollment. Bill Vaughn continued to expand the horizons of the university while on the Board of Trust, much like his grandfather and his Aunt Stella had done in earlier times.

Bill Vaughn is described by those who knew him as a quiet and unassuming person, recognized by all for his brilliance, vision, wit, and unfailingly good manners. A business associate once said, “He begets cooperation. He persuades people to give. He listens.” These attributes were much needed by the Board of Trust during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, when life was changing dramatically and often violently on campuses throughout the United States.

Bill Vaughn’s career moved along at a brisk pace at Eastman Kodak. After serving in many Kodak departments in New York, Europe, and Tennessee, the company named him president in 1960 and chairman of the board in 1967. During this time, Vaughn was an active participant in his community. He was a trustee of the University of Rochester, chairman of the board of directors of the Colgate Rochester Divinity School, a trustee of Eastman House, and a member of the board of managers of the Eastman School of Music. He served as the director of the Rochester Chapter of the NAACP and was a member of the National Council of the United Negro College Fund. His experiences brought important in sights to the Vanderbilt Board of Trust. Former Chancellor Alexander Heard wrote of Bill Vaughn, “His tenure as president included extraordinarily difficult years of campus tension, during which his poise, wide-ranging experience, Intellectual powers, and sagacity made him of prodigious value to Vanderbilt, and especially to me.”

The composition of the Board of Trust at Vanderbilt began to shift during Bill Vaughn’s tenure. In 1964, the Board took the daring (or so it seemed to some) decision to elect its first female trustee, Mary Jane Werthan; in 1968, the Board approved a new group of trustees made up of four recent Vanderbilt graduates. In the first year of the program, four young board members were nominated, with terms from one to four years. Of the four, three were women; by 1970, the students had also nominated Vanderbilt’s first black trustee.

Toward Today

During the 1950s and 1960s, the civil rights movement forced the university to face the issue of racial integration on the campus. The university first admitted black students to attend its professional schools in 1953, although they were not allowed to live on campus and were discouraged from eating in student cafeterias or participating in intramural sports. Efforts to mute the issue of race failed when Vanderbilt was launched into the national limelight after an African American student, James Lawson, was expelled from the Divinity School in 1960 for his role in the sit-in movement at Nashville. Hence faculty recommended by a vote of 79 to 27 that the college admit students regardless of race.

In the 1961-62 academic year, rumblings of change were evident. By this time, Tennessee public universities had begun integrating. The Hustler editor and future Tennessee governor Lamar Alexander advocated open admission at Vanderbilt. The student body was less favorable; in a referendum in February 1962, students opposed open admission by a vote of 862 to 661. Before the May 1962 board meeting, Chancellor Harvie Branscomb and Board President Harold S. Vanderbilt carefully paved the way for a favorable vote on the issue of open admission. It was William S. Vaughn’s strong voice that moved the resolution that would allow entry to all schools and colleges of the university “without regard to race or creed.” The motion passed.

Bill Vaughn was also concerned about educational opportunities for women. Not surprising, given the remarkable women in his family: his Aunt Stella, his wife Elizabeth, and his daughters Janice and Helen. During his term as president of the Board of Trust, the board voted to phase out the previously existing quota system for women students. In a speech to the Alumni Association in 1975, Bill Vaughn observed:

Co-eds here got a late start, for they did not crack what would now be termed the male chauvinist barrier until Vanderbilt was some 20 years old. Even then, the number of women admitted was quite limited, as you know. In May of 1972, the Board of Trust approved the progressive relaxation of the limiting ratio then existing for admission of freshmen to the College of Arts and Science.

Legacies

Bill Vaughn loved Vanderbilt. He never flinched from what he saw as his “due” to the institution. When asked by the university in 1985 to consider making a contribution that would allow the renovation of Residence Five, he agreed to do so. He later remarked that when Vice-Chancellor John Beasley first approached him about the renovation of the home, “I came to attention. The bait was most alluring, even though the embedded hook was plainly to be seen.” He wrote a letter to his brothers and cousins regarding the Vaughn Home project: “The more I thought of it, the more appealing it seemed. Not only were there sentimental reasons involved, but I owe the university an incalculable debt of gratitude.”

In 1985, William S. Vaughn and his brother Houghton committed the $350,000 necessary to complete the renovations of the Vaughn Home. In 1991, William S. Vaughn donated another $150,000 to the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities to assist with necessary matching funds for a Challenge Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

William Scott Vaughn died September 20, 1996. Much at Vanderbilt had changed since his grandfather began teaching classes at the school in 1882; many of those changes had been ushered in under the leadership of Stella Scott Vaughn and William S. Vaughn. The family’s 114-year history with Vanderbilt has had an immeasurable impact on the continuing development and success of the university. Vice-Chancellor Madison Sarratt once introduced Robert Penn Warren: “Universities have no light of their own. Like the moon, they shine only by reflected light. Whatever brilliancy Vanderbilt has comes from her alumni.” Surely the Vaughn family–William James Vaughn, Stella Scott Vaughn, and William Scott Vaughn–have added significantly to the brilliance of Vanderbilt’s reflective light.

Written by Mona C. Frederick, Inaugural Director of the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities, 1997. Material for this article was drawn from a variety of sources, including Paul K. Conkin’s Gone with the Ivy: A Biography of Vanderbilt University, Alexander Heard’s Speaking of the University: Two Decades at Vanderbilt, Edwin Mims’ History of Vanderbilt University, the Vaughn family scrapbooks, the Vanderbilt Alumnus and the Vanderbilt Magazine, minutes of the Vanderbilt University Board of Trust, and personal interviews.