Climate Change

Climate Change – The Basics

What is “climate change”?

The effects of climate change are becoming more apparent to everyone as weather events become more extreme and more often so. The most noticeable extreme weather events include a record number and greater intensity of storms, hurricanes, flooding, heat waves, droughts, and wildfires. Increases in average global temperatures also cause decreased snow cover, shrinking glaciers and ice sheets, accompanied by sea level rise.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines what is also referred to as global warming as “an increase in combined surface air and sea surface temperatures averaged over the globe and over a 30-year period”.

But the Earth’s climate has always been fluctuating and there have always been storms, floods, and wildfires, haven’t there? Yes, but there is more to it:

Throughout the Earth’s history our planet has experienced Ice Ages with severe cooling and glacial expansions, as well as greenhouse periods due to the extreme movement of the Earth tectonic plates and high quantities of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere resulting from volcanic activity. Neither of those two extremes is particularly hospitable to human life on Earth as explained in “The Goldilocks Problem: Climatic Evolution and Long-Term Habitability of Terrestrial Planets”.1 ASCEND Initiative member Professor Jonathan Gilligan explains the need for this narrow habitable climate range in his open-source teaching resources in greater detail.

What causes climate change?

Joseph Fourier discovered in the early 19th century that the Earth has an invisible envelope that protects the planet from the cold temperatures of the outer space (-455°F) and is in its properties similar to a greenhouse: 1) allowing radiant solar heat to warm the planet during the day and 2) preventing that warmth from escaping too quickly during the night. What we now call the atmosphere Fourier established had been balancing incoming and outgoing heat perfectly. However, Fourier did not yet understand what the atmosphere consisted of.

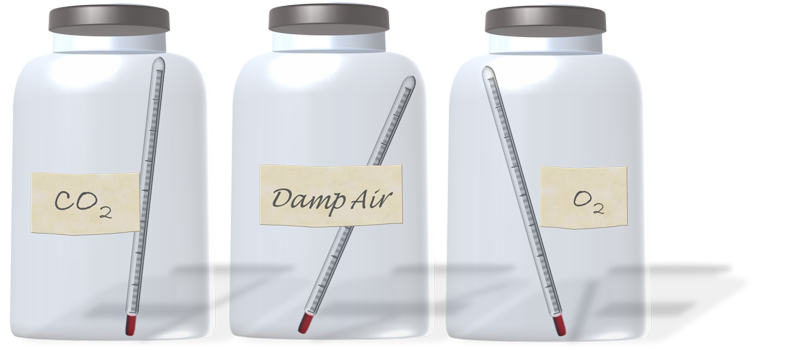

In the 1850s climate scientist Eunice Foote noticed that certain gases captured in jars and placed in sunlight are capable of heating up significantly more than others (Figure 1). She discovered what we now call greenhouse-gases.

Most of Earth’s smaller, natural climate fluctuations have been caused by “natural” changes such as slight changes in the Earth’s orbit around the sun, the energy coming from the sun, or volcanic eruptions. However, we know from deep drilling of ice core samples that are several hundred thousand years old, as well as from many other scientific measures that atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide, one of the major greenhouse gases, have never been higher.

Water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), ozone (O3), nitrous oxide (N2O), various fluorocarbons (FCs), and carbon monoxide are the most common greenhouse gases. While water vapor is the most abundant greenhouse gas (GHG), carbon dioxide is the one whose concentration in the atmosphere has increased most markedly and is released in great quantities by human activity from its natural stores.

However, based on what Eunice Foote already discovered in the 19th century, these different greenhouse gases have different heating potentials (referred to today as global warming potential). The global warming potential of the various greenhouse gases is used to calculate their carbon dioxide equivalent by multiplying it with each gas’ abundance. As such, the concentration of nitrous oxide, for example, is only one-thousandth that of CO2 but it has 265 times the global warming potential over 100 years.

Carbon is stored naturally in plants, soil, and aquatic environments as organic matter, gaseous carbon dioxide, fossil fuels (i.e., petroleum, coal, natural gas, and peat), and as carbonates (when combined with minerals). Therefore, burning fossil fuels for energy consumption, including for transportation, heating & cooling, and electricity releases large amounts of this greenhouse gas into our planet’s atmosphere.

Besides extreme weather, what other effects are there?

Human Health. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization clearly outline urgent threats to human health that are on the rise due to climate change. These include:

- The geographic range of so-called vectors (e.g., mosquitoes, fleas, and ticks) that spread diseases like Lyme, West Nile virus, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and even plague is enlarged due to warmer, wetter weather.

- With flooding events and hurricanes comes pollution of our drinking waters that is difficult to remedy once it has occurred. In addition, most homeowners insurances do not cover the cost of flood damage and living in a flood-damaged building can lead to respiratory illnesses caused by mold.

- Pathogens such as Salmonella and toxic algal blooms grow more easily with warmer temperatures.

- Illnesses and death from extreme heat exposures as new record temperatures are recorded across the globe.

- Air-pollution from wildfires and ground-level ozone cause an increase in many health problems.

Biodiversity. Human activity such as exploitative land-use, water extraction, and increased use of pesticides and herbicides have led to international research showing that more than a quarter of species on our planet currently face extinction.2 Climate change and the extreme weather events that it causes, such as longer droughts and increased wildfire risks, only add to these existing threats to biodiversity as they amplify habitat loss and loss of life. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) estimates that in 2020 wildfires in Australia burned approximately 26.4 million acres and killed or displaced nearly 3 billion animals.

Food Security. Because climate change causes weather events to become more severe (e.g., more intense storms, more frequent flooding, droughts, extreme temperatures), another effect is a decline in agricultural productivity as it becomes more difficult to grow healthy crops under these conditions. Read more about this topic on the USDA website.

National Defense. A 2019 report by the U.S. Pentagon reports of extensive threats to military installations due to fast-paced climate change effects that include recurring flooding, drought exposures, and wildfire risks. Climate change, therefore, poses a direct threat to our national security.

In summary, climate change directly affects many aspects of our daily lives. How big this impact will be may well depend on how boldly we respond to this global threat.

Why can I not worry about this later?

As outlined in the EPA’s 2017 Climate Change Impacts and Risk Analysis report and summarized by Yale Climate Connections, if we continue to do little to address the global climate change threat, damages and losses in productivity from climate change will cost the United States economy hundreds of billions of dollars each year by 2090.

As our planet’s climate continues to heat up, a cascade of chain reactions will make our situation worse if we do not act with sufficient commitment and urgency:

- As wildfires become more frequent and severe, they also release vast amounts of additional greenhouse gases (and other pollutants) into the atmosphere.3 As permafrost melts it releases more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.4

- In addition, ice has a high reflective index called the ice-albedo effect.

- As large ice sheets and glaciers continue to melt, they are replaced by the darker, less reflective surfaces below, which will absorb more of the sun’s radiant heat.

What scientific and technological advances are being globally investigated?

Scientists and researchers in countries across the world have been working for many years to better understand the effects and define potential solutions to this global threat. After thorough risk assessments and review of over 6000 scientific publications, experts from 40 countries, including the United States, agree and summarize in the IPCC Special Report Global Warming of 1.5°C that the response needed will require far-reaching societal changes. These responses include governmental policy changes to put a price tag on pollution; investing in energy efficiency and low-carbon energy technologies; and continuing technological advances that allow us to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, electricity, industrial processes, land-use and agriculture, and landfills.

However, this international report also outlines that limiting greenhouse gas emissions alone will not be sufficient in order to limit global warming to 1.5°C (2.7°F). We will need to continue the development and application of carbon dioxide removal technologies such as reforestation, land restoration, soil carbon sequestration, and direct air carbon capture and storage.

As such, the threat of climate change also offers many opportunities: to be global leaders in this innovation challenge, harness the benefits for human and environmental health, and minimize the economic impact that otherwise will result from increasingly devastating extreme weather events and other negative effects.

What can I do to help?

The problems caused by global warming and climate change may seem daunting. Yet there are many ways that each one of us can make a difference as an individual:

- Help others understand climate change and interest them in learning more. Perhaps even join a local initiative to demand change together.

- Vote for local, state, and national elected officials that support sweeping efforts to combat climate change. Addressing climate change can have many economic benefits but it requires changes in the way we do thing.

- Don’t wait for regulators to make changes for you. Minimize your own carbon footprint and that of your family by reducing energy consumption, product consumption, and waste. Many of these simple changes can also save you money such as low-cost ways to make your home more energy efficient or reducing the number of trips to the grocery store. The EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator lets you see how much greenhouse gas to create or save.

- Become part of sustainability efforts led by Vanderbilt by supporting the ASCEND Initiative.

Read about Vanderbilt’s commitment to use 100% renewable energy by 2023 and achieve zero waste by 2030.

References

- Rampino MR, Caldeira K (1994). The Goldilocks problem: Climatic evolution and long-term habitability of terrestrial planets. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 32, 83–114.

- Díaz-Reviriego, I., Turnhout, E. & Beck, S. Participation and inclusiveness in the Intergovernmental Science–Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Nature Sustainability 2, 457–464 (2019).

- Loehman, R.A. Drivers of wildfire carbon emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 1070–1071 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00922-6

- MacDougall, A., Avis, C. & Weaver, A. Significant contribution to climate warming from the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature Geosci 5, 719–721 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1573