Island Soldiers – Keezia Dotimas

Island Soldiers: Situating the Body as a Site for Colonial Resistance

Keezia Dotimas

Keezia Dotimas is a student leader at Vanderbilt who is most active within the spaces of creating a sense of Pacific-Islander and Filipnx cultural pride. She is at the forefront of exploring how art can be used as a tool to create material realities for the lived experiences of indigeneity as well as its futurity. Through her globalized upbringing as a Filipinx immigrant in Guam, she uses her art as an extension of understanding the complex histories of the Pacific Islands’ hyper-militarization and the movement of the Filipinx diaspora across the globe as informed by labor.

Keezia’s main form of medium is graphic design as she also believes in the democratization of information in our increasingly digitized world. She has been also experimenting with printmaking, laser etching, and using different approaches and materials to investigate how her designs can manifest into tangible objects beyond the traditional modalities of printing.

She is deeply motivated by the investigation of histories and their potential to shape the ways Indigenous communities project their futurities in the present. Through her art, she challenges the anachronistic impositions of censorship and asserts that communities can indeed move forward. Her collaborations with initiatives like the Black Peabody Museum and Imagining America seek to create art that highlights the impacts of historical events that continue to shape the present.

About the installation:

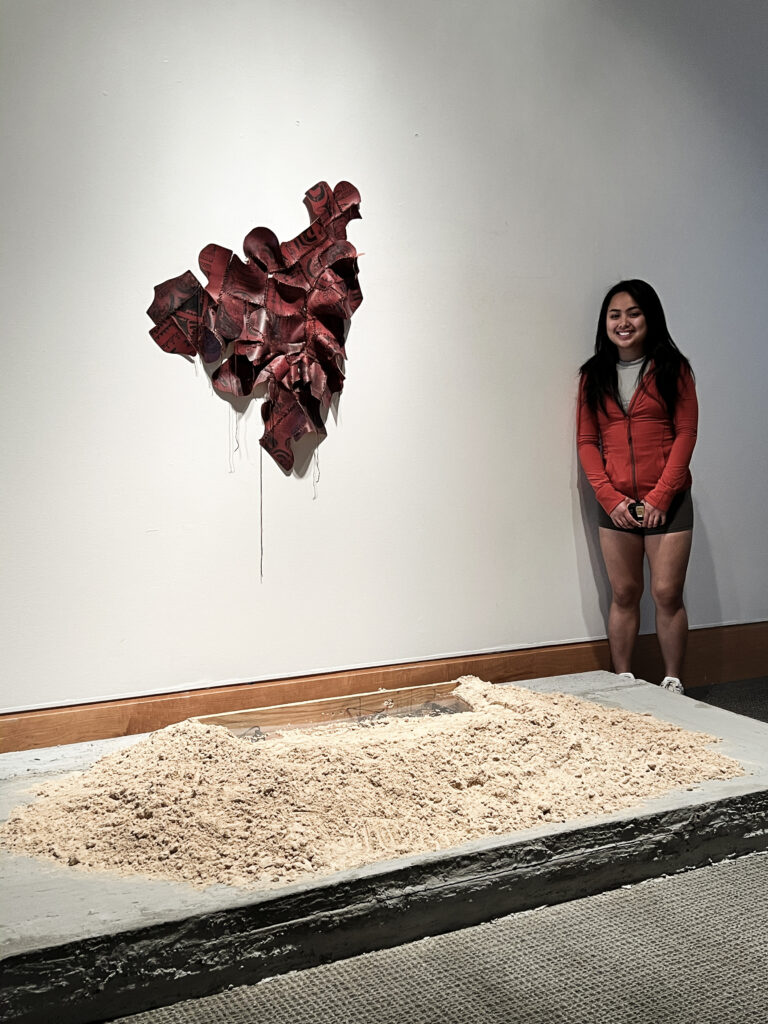

My thesis exhibition explores the intersection of the body as the site of culture and militarization. Central to the work are two pieces: a mosaic of tattooed skins sewn together, and a sand machine that depicts different Oceanic tribal tattoos. The diptych draws on the legacy of traditional tribal tattoos from Oceania.

The tattooed material is similar to human skin in visual and physical characteristics. The “skins” take form in shapes that make up different parts of the body where the tattoo would traditionally be placed. By using skin-like material, I strive to convey the manipulation and elasticity of both skin and culture. Pieces sewn together evoke the discomfort of colonialism, where Oceanic cultures are stitched into place and forced to adapt. Yet, they remain flexible- offering both forms of adaptability as resistance and submission. These “skins” speak to the underpinnings of opposing cultural censorship and reclaiming the traditional practice of tattooing. They are connected in discombobulation, body parts disjoined from one other: a distinct representation of the impact of centuries of erasure.

Perpendicular to the wall that holds the skins sits a sand machine built using found materials across Vanderbilt campus. The machine sits on a pedestal of concrete, symbolizing the ways the military has rooted itself in the island. It reflects the appropriation of indigenous lands for military bases and the imposition of an economic system shaped by policies like the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, which regulates maritime commerce in U.S. waters and between U.S. ports. This system, in turn, facilitates the flow of goods into the islands under the watchful eye of the U.S. military. In the box itself, the sand machine uses Arduino code to replicate patterns of traditional tribal tattoos across Oceania, spanning Samoa to Guam to Hawai’i to the Philippines.. The code is then translated into movement using mechatronics and magnetism; a ball sits atop the bed of sand to compose the patterns. The box, a harsh, delineated structure, evokes military control. Submerged beneath a cascade of sand, its boundaries become less distinct. With the box, I represent the precise militarization of Island folk enmeshed with the U.S. military-industrial complex. Within the box, electronic mechanisms alter the trajectory of the magnetic ball above, mirroring the transformation of a trained soldier– one whose indigeneity has been drilled down only to be built back up to become the model American soldier. The magnetic device controlling the ball’s path symbolizes the polarizing process of enlistment: to serve the country that occupies your land while simultaneously wearing a form of that culture’s expression in service. By using these methods, I chose sand to symbolize militarized bodies, with the box serving as a representation of a site where cultural expression is both confined and manipulated. Sand spilling from the machine also evokes the blurring of these boundaries, capturing the complex conversation around the American militarization of Oceania and the role of its Island soldiers.

Tattooed skins and the sand machine are in conversation. The skins represent the desire to resist censorship and reclaim traditional practices, while the sand machine critiques the process of using the body as a tool of resistance, even when it comes to the contradiction of military service. Though they exist side by side, they never physically interact—symbolizing the disconnect between cultural expression and militarization. This separation challenges the viewer to reflect on the nuanced and polarizing process of occupying multiple identities: as Indigenous peoples resisting cultural erasure yet simultaneously participating in the forces that have historically oppressed them.

The exhibition intentionally leaves the question unanswered: What is the future of these identities, and how do we engage with this history? In not offering clear resolutions, the work invites the viewer to contemplate the ongoing conversation between cultural preservation and the forces of militarization and to consider their role in this complex narrative.

This installation: