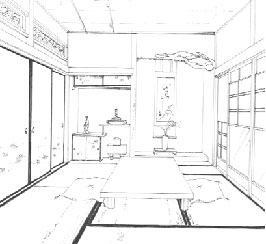

Roland Barthes, on traditional Japanese houses:

"And so that we may see how it is put together, let

it be illustrated by the Shikidai corridor: papered with opening, framed

by empty space and framing nothing, decorated, it is true, but in such

a way that the figuration (flowers, trees, birds, animals) is swept away,

sublimated, shifted far from the forefront of vision.  .

. in this corridor, as in the ideal Japanese house, devoid or nearly so,

of furniture, there is no place which in any way designates property;

no seat, no bed, no table provides a point from which the body may constitute

itself as subject (or master) of space. The very concept of centre isrejected

(a burning frustration for Western Man, everywhere provided with his arm-chair

and his bed, the owner of a domestic position). Non-centered, this space

is also reversible: you can turn the Shikidai corridor upside down and

nothing will happen other than an inconsequential inversion of high and

low, right and left. Content has been irrevocably dismissed: whether we

pass through, or sit on the floor (or ceiling, if you turn the picture

around) there is nothing to grasp." .

. in this corridor, as in the ideal Japanese house, devoid or nearly so,

of furniture, there is no place which in any way designates property;

no seat, no bed, no table provides a point from which the body may constitute

itself as subject (or master) of space. The very concept of centre isrejected

(a burning frustration for Western Man, everywhere provided with his arm-chair

and his bed, the owner of a domestic position). Non-centered, this space

is also reversible: you can turn the Shikidai corridor upside down and

nothing will happen other than an inconsequential inversion of high and

low, right and left. Content has been irrevocably dismissed: whether we

pass through, or sit on the floor (or ceiling, if you turn the picture

around) there is nothing to grasp."

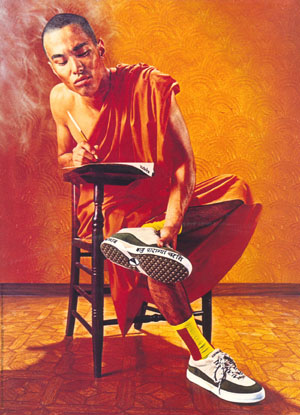

Ernst Earle, on social coherence and traditional Japanese culture:

"Wealth could provide greater abundance of food and

better quality materials; it could purchase nothing essentially different

in from or function. The code of morality and social behavior . . . at

last permeated into all social groups, so that finally the Edo fireman

shared an ethical climate not immediately distinguishable from that of

the samurai.

Similarly, tastes in art were built up out of commonly

shared artistic experiences . . . Identical tastes in music and in the

graphic arts were so widespread that, until modern times, the body of

artistic canon did not differ significantly according to social stratification.

A maid serving tea moved in a style similar to that used at court ceremonies;

shop clerks were taught to sit, move, and stand in patterns used in the

No and were intensively drilled to speak in a manner closely resembling

that of the Kabuki actor."

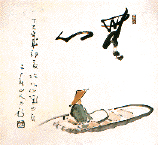

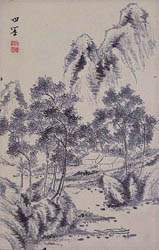

Kato Shuichi, on form, style and tradition in Japanese art

"Different types of art, generated in different periods,

did not supplant each other, but coexisted and remained more or less creative

from the time of their first appearance up to our time. Buddhist statues,

a major genre of artistic  expression

in the period from the sixth to the ninth century, continued to evolve

in style during the following eras, even when the picture scroll opened

newpossibilities for the visual representation of the world in the Heian

period. Brush works with india ink flourished during the Muromachi period

[1336-1573], but one school of artists remained faithful to the techniques

and style of the picture scroll . . . Artists never ceased to carve Buddhist

statues or engage with great passion in brush-work painting. Practically

no style ever died. In other words, the history of Japanese art is not

one of succession but one of superimposition." expression

in the period from the sixth to the ninth century, continued to evolve

in style during the following eras, even when the picture scroll opened

newpossibilities for the visual representation of the world in the Heian

period. Brush works with india ink flourished during the Muromachi period

[1336-1573], but one school of artists remained faithful to the techniques

and style of the picture scroll . . . Artists never ceased to carve Buddhist

statues or engage with great passion in brush-work painting. Practically

no style ever died. In other words, the history of Japanese art is not

one of succession but one of superimposition."

Text, Image, and Pictorial Surface

|