Adam Valencic

Medical Art:� The Surgeon and the

Painter

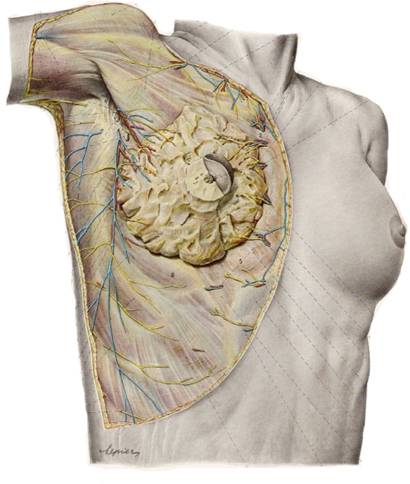

Eduard Pernkopfs Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy utilizes a team of skilled artists to render in fine detail the anatomy of the human body. Placing aside the utilitarian aspects for which these paintings were compiled, each piece stands as a work of meticulously created art. Austrian born Erich Lepier, an artist in his own right, became one of the first to work alongside Pernkopf, thirteen years before Pernkopf assumed the position of Dean at the famed Anatomy Institute of the University of Vienna in 1938 (Williams). Removing this piece of art from the medical context, the beauty of the piece can more readily be appreciated.

Lepier, using a combination of graphite and watercolor, renders the female human body in exquisite detail. The right side of the breast is laid bare with more attention drawn to it as the only area of the artwork rendered with color. Most notable is Lepiers use of delicate pastels to shade in the musculature of the female subject. Clinical motivations perhaps play a greater role in the demarcation of the veins in bright, individually distinguishable primary colors, as is the yellowing of the fatty memory tissue of the exposed breast, but Lepiers decision to color in the background musculature in a painstakingly fragile manner is both unique compared to Lepiers other medical paintings as well as completely unnecessary for the work as an object of the textbook.

Susan Buck-Morss, in her Aesthetics and Anaesthetics: Walter Benjamins Artwork Essay Reconsidered, works through Benjamins critique of art as it emerges from the Industrial Revolution and begins its journey through a new Technological Revolution. She writes:

Benjamin is saying that sensory alienation lies at the source of the aestheticization of politics . . . We are to assume that both alienation and aestheticized politics as the sensual conditions of modernity outlive fascism and thus so does the enjoyment taken in viewing our own destruction . . . He is demanding of art a task far more difficult that is, to undo the alienation of the corporeal sensorium, to restore the instinctual power of the human bodily senses for the sake of humanitys self-preservation, and to do this, not by avoiding the new technologies, but by passing through them. (4-5)

Benjamins critique and his hope for the future of art provide two distinct approaches to Lepiers artwork. It may be seen as either an example of the deaestheticization caused by sensory alienation, or the opposite, an answer to Benjamins call for the future task of art.

Benjamin analogizes the work of the painter as compared to the cameraman as similar to the comparison between magician/ healer and surgeon. The magician and the painter both maintain a natural distance from reality but the cameraman offers a thoroughgoing permeation of reality with mechanical equipment, an aspect of reality which is free of all equipment (Benjamin 233-34). Lepiers work walks a strange and careful line between these polar opposites. On the one hand, we have the role of the painter, maintaining proper distance from the body, yet at the same time, being intimately aware of the aesthetics of the body. On the other hand, Lepier takes on the role of the surgeon, using brush as scalpel to cut away the external body and permeate the flesh below, but ultimately deaestheticizing his reactions to the body.

As a painter, Lepiers work of art in question shows a subtle relationship with the human body. Life is breathed into the painting only in its exposure of the inner body. Again, the soft hues of color of the subjects musculature give the appearance of warmth through the predominance of the reds and yellows over the blues. Externally, the body in the painting is dead. The mute grays of the skin are dull and lifeless. There is only the torso, immobilized without arms or legs, unable to speak or think, being without a head or face. This, it must be noted, is not merely for the purpose of the textbook, as Lepier has other works in the same volume that include these absent limbs and parts. Stripped of all possible thoughts, actions, and external reality, the exclusion of these body parts, so essential to life, only heightens Lepiers focus on the body as a body.

As a surgeon, however, Lepier delves into the subject with cold clinical precision and dexterity. Susan Buck-Morss describes the process by which people seek to anaesthetize themselves from shock of over-perception and cognition (18). In this way, Lepiers work can be seen as an attempt to remove from himself any part of his female subject which would allow him or anyone else to identify with the subject as a human body. By cutting away all but the torso, Lepier has left his name as the sole identifying mark on his subject. She has no access to any of the sensory functions crucial to the aesthetic process.

Erich Lepier does not clearly give evidence in this work of art as to which side of Benjamins artistic line he stands on. Rather, Lepiers work seems to stand directly on the line between sensory alienation and perceptive acuity. But there is still one important aspect of this work to discuss, its context. This is not the context of the work as it pertains to its place in medicine, but rather the cultural surroundings in which it was created.

It would be wonderful to analyze this work of art in a context other than that of its reality, or to invent a context that creates a touching backdrop for the painting. This, however, is not the case. Eduard Pernkopf was undisputedly a Nazi official. His wish, when he became Dean of his university, was to create not just doctors, but Nazi doctors; doctors who would fully be in line with the Nazi ideology of racial purity and hygiene. His team of artists were also all affiliated with the Nazi party. One artist, K. Entdresser, occasionally replaced the double-S of his surname with the twin lightning bolts of the Schutzstaffel. Erich Lepier frequently included a small swastika next to his signature, which later editions airbrushed out. It is unclear exactly what the origins are of the specimens from which these drawings are taken, but it is surmised that a large portion of the bodies were those of criminals executed by the Nazi State, with a small percentage of those being Jewish Holocaust victims.

How then do Benjamins modes of artistic reproduction function within the framework of this context? If Lepier viewed his subjects with acute awareness of their humanity and their corporeal bodies, it shows incredible cruelty. If he viewed his subjects as not even registering as human, it demonstrates an inhumane depravity. Or is it most bothersome that I, knowing the origins of his work, still grant it the title of art? For me, there is no answer, and most likely never will be. More so than the painting itself, I find appealing the conflict engendered in my own consciousness and conscience when viewing this piece. In the preface to the work the editor writes that this work could only have been achieved through the combination of numerous, particularly fortunate circumstances (IV). Every time I read this I am conterminously sickened by the implications and drawn towards the artistry of the work. It is a work of art which holds in itself, through its beauty and its context, both the enjoyment taken in viewing our own destruction as well as fulfilling Benjamins hope that art will undo the alienation of the corporeal sensorium, to restore the instinctual power of the human bodily senses for the sake of humanitys self-preservation (Buck-Morss 4-5).

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zohn. The Work of Art in the Age

of Mechanical Reproduction.

Buck-Morss, Susan. Aesthetics and Anaesthetics: Walter Benjamins Artwork Essay Reconsidered. October 62 (Fall 1992): 3-41.

Pernkopf, Eduard. Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human

Anatomy: Volume Two, Thorax, Abdomen, and Extremities. Ed. Dr. Helmut Ferner. Trans. Dr. Harry Monsen.

Williams, David J. The History of Eduard Pernkopf's Topographische Anatomie des Menschen. Journal of Biocommunication, Volume 15, Number 2, Spring 1988, pp. 2-12. (http://www.vet.purdue.edu/brad/medill/pernkopf.html)