Nancy Twilley

Jenny Holzer

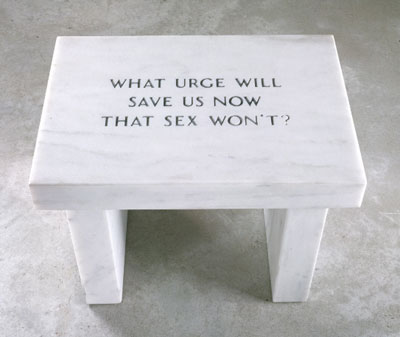

Survival Series: �What urge will save us now that sex wont?

1983-85

Most of Jenny Holzers work

involves text printed or inscribed on an object. She is most famous for her Truisms series,

a collection of pithy statements which have been printed on t-shirts, displayed

on

While one might call the bench beautiful because of its simplicity, pure color, or symmetry, the work as a whole fits uneasily into the category of beauty. In a Kantian sense, a consideration of the benchs beauty must also consider its message which mars its appreciation. The work is certainly agreeable by his definitions as it is generally pleasing to the senses. But this is only a remark on the observing subject, and not purely on the object itself. The bench is furthermore good in a Kantian sense as its message is reasonable and useful, pointing out something Holzer sees as a social problem and giving the work direction. But the fact that it bears a message, a message which is in fact central to the work, determining the form of the bench on which it is inscribed, makes it impossible for this piece to be beautiful.

For Kant, beauty, unlike agreeableness, must be the property of an object and not the result of a relationship between subject and object. A beautiful thing must be universally praised as such and freely appreciated by all as beautiful. A judgment of what is beautiful may involve logic, for as the pleasure derived from contemplating a beautiful thing causes the observer to want to imitate it or seek it out repeatedly, one can make generalizations about the beauty of a class of objects if one is found to be beautiful. But the appreciation or identification of beauty can never involve a consideration of its use value or message. The bench, however, may be considered beautiful. Its marble has what Kant might call a pure color, and its form is regular and appreciable. As a bench it has a sort of dependent beauty, as it is an example of perfect regularity and possesses all the qualities it is supposed to have. As a bench, it approaches perfection. As an artwork, perhaps, it could have a sort of free beauty, as an artwork is not supposed to have any particular shape but can be simply appreciated without prior experience of other art. The bench could not, however, be considered beautiful as a practical object, as no consideration of an objects utility contributes to its beauty. These observations, of course, presuppose a common sense or common and deep-seated taste whereby all people would judge the bench as an object as I have. Not everyone will always agree on the beauty of a particular object, but we can say with some finality and in light of the given reasons that everyone ought to agree on this bench as beautiful. My private feelings may tell me that this object is beautiful, but I must compare those to a public sense in order to make such a declaration.

The benchs message may also be called both agreeable and good, but not beautiful. No written work may be called beautiful for its message, although it may be appreciated for its form or the sensations it produces in the reading or listening subject. A poem, for instance, may be beautiful because of its cadence or rhyme scheme, and indeed the form of a written work is key to its beauty. The form of this message may be beautiful: its symmetry, brevity, position on the bench, and skillful carving all attract the viewer. As an idea, however, the text, and by extension the bench, are not beautiful.