Frizzi Strube

As the task of this position paper is to �discuss

the articulation of beauty in one specific work of art we must first ask

ourselves one question when dealing with Leni Riefenstahls documentary

In the opening scene the spectator finds

himself in Greek antiquity accompanied by archaic music. The scenery remains

dark, which is not only due to the poor quality of the cinematography or the

fact that this movie is shot in black and white, but rather to accomplish a

vague and unrealistic setting. Greek temples and statues are shown, surrounded

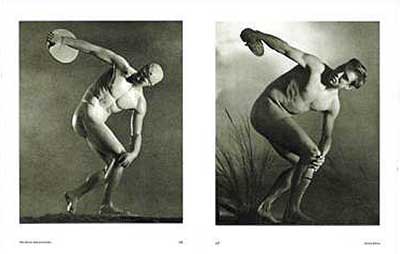

by clouds of fog which cause a mystic effect. Myrons famous statue Discobolus

(5th century B.C.) finally turnes into a living athlete, naked,

rotating around his own center of gravity, throwing the discus. Not only does

this image make the connection between the ancient Olympic games and the games of

the modern times, it introduces the whole documentarys main focus: the human

body. Of course it is an extraordinarily beautiful male body to which the

viewer is exposed, a body that even most discus-throwers do not have as one can

notice all throughout the documentary. Gumbrecht says in his book: [...] the

best anatomical model is not necessarily the one with the largest muscles. It

is a shape in which the development of each individual muscle does not spoil

but rather enhances a difficult-to-define impression of harmony.[2]

This harmony can certainly be found in the living Discobolus. The athletes movements

show a high degree of perfection, his body is beautiful because the body itself

as well as its movements are flawless.

Although it is completely uncovered, it does not necessarily give rise to sexual

fascination, the feeling of beauty is rather evoked by the bodys strength, its

skills and, most importantly, its capacity as an athletic tool. In this opening

scene Riefenstahl intends to demonstrate and idealize the human body, an effect

that is not easy to achieve anymore in the context of the actual athletic

performances in the competitions of 1936.

By the first discipline documented in the movie

again discus-throwing the viewer learns that the bodies of the athletes do

not necessarily correspond with the stylized body demonstrated in the opening

scene. They are not always perfect, some sportsmen are smaller than Discobolus,

while others lack his beautifully defined muscles. Some athletes even appear

goofy especially for the viewer of the 21. century for example in looking at

their wide jerseys. It is perhaps to compensate for these shortcomings that

Riefenstahl uses techniques such as slow motion, drawing the viewers attention

to the execution of movements. The viewer is thereby able to take his time and

focus precisely on actions that normally are over too rapidly to be properly

understood. When criticized for the too frequent use of slow motion,

Riefenstahl answered:

It is precisely these

shots that give the film its artistic worth. They were employed according to

laws of art and rhythm. Never before or since has this principle of

individiually various shot tempi been employed, because it is extremely

difficult, artistically and technically.[3]

One could actually argue, that the slow motion

shots together with the music by Herbert Windt a popular film score composer in

the Third Reich, especially for propaganda films are among the only, for the

naive viewer noticable artistic intruments used by Riefenstahl. In the movie these

instruments are used to emphasize the athletes actions and movements and

thereby excite a better understanding, appreciation and enthusiasm within the

viewer, who is watching the movie in the movie theatre or nowadays on

television and is therefore lacking the actual experience among the cheering crowd

in the Olympic stadium in

Riefenstahl suggests two different concepts of

beauty. With the stylized opening scene she puts forward the image of the ideal

(athletic) human body, whereas the actual documentary has to deal with real

human bodies, which appearently need to be increased in value through slow

motion and music. Riefenstahl was praised for applying those techniques and making

visible certain components and details not recognizable for the human eye under

normal circumstances; and the viewer cannot deny the special impact. But it is

also questionable if the human body really needs to be beautified at all.