Ian Schatzberg

Position Paper

Between Heidegger and Felix Gonzalez-Torres

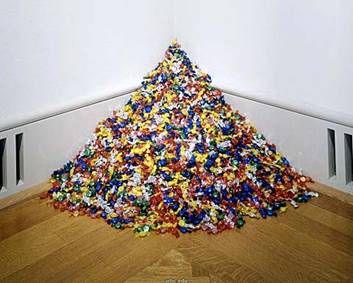

Dozens of hard, sugar candies are piled on top of each other wrapped in multi-colored cellophane. Positioned against the corner of a white gallery wall, these candies, from a distance, resemble a garbage mound on a New York City sidewalk. Their undefined shape suggests nothing unique about Felix Gonzalez-Torres installation piece, Untitled (Ross) 1991. However, standing above the glistening sheen of the candies makes us feel as though we were in the presence of treasure rather than refuse. Buried within this mound Gonzalez-Torres conceals the company of his lover and a vision for remembrance.

Untitled (Ross) challenges the conception of the artwork as articulated by Martin Heidegger in The Origin of the Work of Art. Blurring the distinctions between Hiedeggers schema of Work/Being/Thing, Gonzalez-Torres piece occupies a curious position in relation to traditional definitions of art. Consequently, Untitled opens up a space from which we may begin to evaluate the tensions between a Heideggerian critique of art and conceptions of art within postmodern production.

Heidegger makes subtle, careful deductions towards establishing the artwork in opposition to other types of works. His writing shows great concern for the ways in which artwork may be conflated with equipment. He comments: On the other hand, equipment displays an affinity with the artwork insofar as it is something produced by the human hand (yet) the piece of equipment is half thing, because characterized by thingliness, and yet it is something more; at the same time it is half artwork and yet something less, because lacking the self-sufficiency of the artwork (155). The crucial factor at play within Heideggers differentiation between equipment and artwork lies in this conception of self-sufficiency. Equipment, by means of its utilitarian nature, cannot occupy the autonomous space envisioned as essential in the life of an artwork. This emphasis on autonomy and distrust of utility places Heidegger within a Kantian aesthetic tradition and distances him from last weeks critic, Walter Benjamin.

Gonzalez-Torres asks that we ingest his artwork. Spectators gather around Untitled (Ross) unwrapping each sugar candy so that they may taste its sweetness and place its exteriors in their pockets as keepsakes. The weight of these candies in total is that of Torress lover Ross, 175 pounds at his ideal weight (Ross died of AIDS and suffered from great amounts of weight loss during his illness). By ingesting these candies the audience essentially ingests a piece of Ross, and in doing so, takes a piece of the deceased along with them throughout life. However, such an act of ingestion also renders this work a piece of equipment.

In the most literal sense, Gonzalez-Torres piece offers its audience subsistence. We ingest the candy and therefore gain whatever its minimal nutritional value may be. Created by the human hand, these candies fulfill Heideggers conception of work; yet as they dissolve in our mouths, we bring forth their utilitarian nature. Furthermore, we rely on these candies in the sense that they may provide us with the materials for our survival. In this manner, Gonzalez-Torres piece expresses these relatively abstract claims: one, that the equipmental being of the equipment consists indeed in its usefulness, and two, that the equipmental being of equipment, reliability, keeps gathered within itself all things according to their manner and extent (160). Through a Heideggerian framework, Untitled (Ross) becomes nothing more than a cite of reliability and usefulness.

The second facet of Heideggers conception of equipmenthis remarks on issues surrounding materialityfurther illuminates the problematic tensions between his philosophical inquiry and Gonzalez-Torres work; meanwhile, it also helps bridge this conversation with larger thematic issues within postmodern art. Heidegger states because it is determined by usefulness and serviceability, equipment takes into its service that of which it consists: the matter. In fabricating equipmente.g. an axstone is used, and used up. It disappears into usefulness (171). While equipment may dissolve material, the true artwork brings materiality forth in a manner incapable of disappearing. Gonzalez-Torres candies clearly demonstrate this theme of a materiality that becomes used up as equipment. His candies literally disappear into subsistence and are forever gone. Yet in their transition from material equipment into the abyss, a symbolic transformation occurs within the spectatora moment in which Heideggers portrayal of the equipmental seems incapable of comprehending.

Clearly, by fulfilling Gonzalez-Torress request that we ingest his artwork, we are also fulfilling the desire that his lover live on in our memories and bodies. Untitled (Ross) performs the type of ceremony we associate with communion and retains an almost religious seriousness about it. While a Heideggarian reading of this piece may level its artistic virtues, it would be naïve to suggest that Gonzalez-Torres work is inartistic.

Untitled (Ross) exists within the gallery space and, although it may demonstrate the characteristics of equipment, its context resists such a reading. Glittering against the severe plaster concrete it lies on, such a work forces us to reconsider the ways in which utility may be less at odds with artistic production within postmodernism. In fact, it is the very utilitarian nature of Gonzalez-Torres piece that constitutes its artistic character. The opportunity to symbolically ingest Ross heightens our experiences of remembrance and physically forces us to confront our loss: we know Ross since we have tasted his sweetness. Without this utilitarian interaction, the intimacy generated by Untitled (Ross) would severely diminish.

While I have begun to suggest that postmodern artists have reconceptualized art as a dialectic between the creation and utilization of works, a critical question remains unanswered: how does the context of a work with a very apparent utilitarian dimension affect our perception of it as an artwork? Without the proper space for contemplation, does such a work as Untitled (Ross) simply become equipment? Pushing forth on these questions will help us better understand the evolution of artistic production and theory since Heideggers The Origin of the Art Work. Furthermore, such consideration may also demonstrate how the production of space has become critical when we no longer ask artworks to demonstrate self-sufficiency.