Necia Chronister

On Beauty

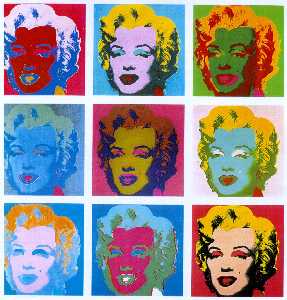

Andy Warhol�s Marilyn

At first glance, Andy Warhols Marilyn series is a colorful, playful take on a pop-culture icon. In this piece, nine images of a coquettish Marilyn Monroe gaze out at the viewer, her hair and make-up in iconic perfection, recreated through screen printing in bright, synthetic colors. As the spectator begins to focus on one or more of the individual panes, however, it becomes clear that this is not the Marilyn Monroe that we know from the movies. Her eyes no longer give that come hither stare, but are rather smudged. Her hair begins to look like a bad wig, and her features appear detached from her face. In Marcuses terms, the Marilyn Monroe of the silver screen belongs to the affirmative culture, meaning that her beauty promises the possibility of happiness without changing the material circumstances of the viewer and without evoking the viewers critical consideration of his own place in capitalist society. Warhols Marilyn does not belong to this culture. His Marilyn is the icon represented in its facticity: the icon that is totally synthetically constructed by the market. I argue that because Warhols Marilyn collapses the distance between the material world and the Ideal, between the facticity of the market and the image of beauty, her image is one that takes a step in eliminating the affirmative culture, and thus performs what Marcuse suggests at the end of his essay.

First and foremost, Warhols work

comments on the violence necessary in creating the icon of beauty and

happiness. He dismantles Marilyns image

violently, dissecting her facial features from one another through the use of

bright, contrasting colors. Her eyes,

lips, and hair stand out as the elements most commodified

by the affirmative culture. Even in the most realistic of the panes, her

hair, lips, and eyes are painted over in wildly synthetic colors. Marilyns natural beauty is not enough, but

must be covered over by lipstick, hair dye, and eye shadow. Marilyns image becomes divorced from her

person, indicating the violence done in

Once we recognize that Warhols Marilyn (and by extension the Marilyn Monroe of the silver screen) is pure vacant image, the icons soul also comes into question. Marcuse discusses the soul as belonging to the realm of the affirmative culture, the only place where feelings of happiness and connectedness can exist in capitalist society. In artistic representations, the soul of the individual is able to connect with other souls (which accounts for the effectiveness of the work of art in an age of the isolated individual). Warhol, however, explodes the possibility of the soul in artistic representation. By revealing Marilyns image for what it ismerely constructed representationhe comments on the impossibility of the market to create an image with a soul. We see this in Marilyns vacant starethe person is no longer person, but merely image, merely bright colors on canvas. Subsequently, Marilyn can no longer satisfy the soul, but rather, activates the critical mind.

At the end of his essay, Marcuse calls for a return to true sensuality, that is, for the individual to stop looking beyond the material world for happiness. To be sure, the Marilyn Monroe of the silver screen represents the kind of timeless beauty and exalted sensuality that function to distract and satisfy those who look to the affirmative culture for happiness. In Warhols piece, this kind of sensuality is revealed for what it is: mere illusion. Her beauty is deflated, reduced to the facticity of the means of its production, as the viewer is reminded of the constructedness of the image. Warhols work performs the first step in eliminating the affirmative culture: it deflates the illusion of happiness that the affirmative culture produces, grounding the viewer again in his/her material world.

Image source: http://neocitrus.hautetfort.com/images/warhol_Marilyn.2.jpg