Joy

Christensen

Position

Paper

Nov.

1, 2006

�So

Many Styrofoam Dots

In his essay The Origin of the work of Art

Martin Heidegger makes the statement that art lets truth originate. Applying

this statement to a personal experience, I recently found myself on a 10-foot

ladder suspended over a gallery, gluing colorful styrofoam balls into a corner with a glue stick. This

was the task assigned to me when I responded to the call for help installing

work for Tom Friedman at the

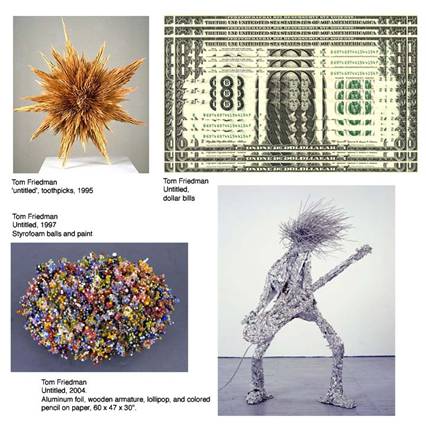

Tom Friedmans work traditionally involves

materials (besides what he collects from his own body), which could be

purchased at any convenience store. He chooses objects that everyone every day,

but tend not to over think, such as toothpaste, tin foil, soap, yarn, or even

dollar bills. The goal then becomes to remove these things from their intended

purpose and turn them into art by way of obsessive manipulation. The resulting

objects are surprising to viewers when they identify the original material; the

time and effort put into the manipulation of the material, and relate it to

their own use of that material in their own daily ritual. Heidegger is

immensely concerned with what he terms the thingliness

of an artwork. He also takes steps to segregate those things that serve as

equipment and those things which function as art. He says,

equipment shares

and affinity with the artwork insofar as it is something produced by the human

hand. However, by its self-sufficient presencing the

work of art is similar rather to the mere thing which has taken shape by itself

and is self-contained. Nevertheless, we do not count such works among mere

things. As a rule it is the use-objects around us that are the nearest and the

proper things. Thus the piece of equipment is half thing, because characterized

by thingliness, and yet it is something more: at the

same time it is half artwork and yet is something less, because lacking the

self-sufficiency of the artwork. Equipment has a peculiar position intermediate

between thing and work, assuming that such a calculated ordering of them is

permissible. (p. 154-155)

Since Friedmans art relies on the viewers

identification of his materials as things from a former life of use-objects,

Heideggers segregation becomes complicated. But Friedman removes the utility

from these objects and forces them to, as Heidegger would call it, loose their

equipmentality and serve an entirely different

purpose. So maybe the truth in Friedmans work actually relies on his

manipulation or working these materials; his work as creator.

Heidegger states, If

there is anything that distinguishes the work as work, it is that the work has

been created. (p. 181) and The workly character of

the work consists of it having been created by the artist. (p.183) Another question unanswered for me concerns the fabrication

of art works. Many artists do not fabricate their own work. It is common for an

artist custom order work from other sites, many times never actually

constructing a work in their own studio. In the case of the Friedman installation,

many interns like myself were used to accomplish the

time consuming gluing that was required. Thankfully Tom Friedman was present

for much of the installation, although, it would not have been outrageous for

him to send directions and/or an assistant to see that things were set up to

specifications. Locating the origin of the work of art seems much more

complicated the farther the artist is removed from the fabrication of the

artwork. While I was the one gluing the styrofoam to

the wall, it gave the construction of the artwork integrity to have Friedmans

own hand start off the progression, and know that he had himself done this many

times before.

The object in contemporary art is becoming

harder and harder to identify.Many artists are no

longer concerned with creating objects at all; instead the goal becomes

creating the conditions for an experience within the viewer. The production of

the work moves beyond the artist to the spectator, relying on their conception

to form the final content of the work. In the case of Friedmans work, this

takes the form of a playful discovery or surprise about how each work was

constructed. A seemingly simple object becomes newly perceived as the result of

obsessive craftsmanship, accomplished with household objects. The thing, be it

a toothpick, a piece of chewing gum, a cereal box, is taken out of its original

function and manipulated to the point of utter confusion. For this reason, I

would say that the origin of the work of art, which Heidegger desires to

pinpoint, very much rests within the viewer. Friedmans work especially relies

on the viewers impression. The work of intricately carving a bust into an

aspirin pill would be lost with no audience to appreciate it. So, I might be

tempted complain about my work in the gallery corner as mundane. Except, the

only other option for work is on the opposite gallery wall, which every other

student is busily working to completely cover with plain white styrofoam balls. Ill keep the

colored ones. Besides, for reasons still more confusing to me, I love the

results of this work. I am repeatedly looking down in wonder at this beautiful

row of colored dots, and not really being able to figure out when my

appreciation for this work appeared, or when I started to find it beautiful.

All quotes taken from:

Heidegger, Martin The Origin of the Work of

Art, from Basic Writings, Ed. David

(pp.141-203)

All images:

http://kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/Friedman.html