Mary Reid Brunstrom

Serra�s Twain: Cant this be replaced with something

beautiful?

This 1986 cartoon

provides a point of departure for consideration of how Richard Serras Twain engages notions of beauty. Occupying an entire city block on the Gateway

Mall in downtown

As the cartoon implies,

Twain signals a violation of public taste,

a transgression attributable chiefly to the rusty quality of the then unconventional

material for art, Cor-ten steel. Terms like junk and scrap metal recur

throughout the public discourse. Twains

eyesore potential is exacerbated by a hubris of scale. Adding insult to injury, successive generations

of graffiti writers have emblazoned messages on its billboard-like plates, ranging

from the insipid--Anna loves Billy to the forceful--GET RID OF THIS THING! Such defacement precludes an appreciation of

the abstract textural beauty in the patterns formed by oxidation runs and

fabrication markings, the Japanese wabi-sabi notion of beauty in imperfection elaborated

by Sartwell. Disfigurement of the

sculpture guarantees that the work will be considered and dismissed over and

over again in the realm of taste. The

record shows that graffiti applications coincided with intensive media coverage

of the rancorous public discourse on Twain.

Graffiti express a need to vent opposition to Twains presence in the public sphere. But a debate that was ostensibly mobilized

around outrage at the ugliness and inappropriateness of the material spilled

over into a far-ranging and long-running discourse encompassing the major issues facing the city

as it transitioned from a vital, well-populated center to a declining urban

core. Hence, Twains polemical inversion of received notions of beauty leads to consequences

in the domains of politics and morality.

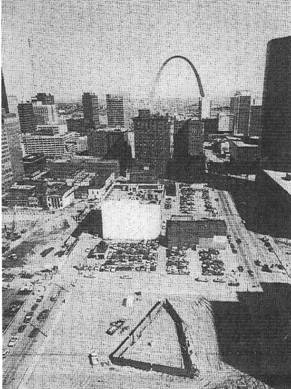

Twain under construction, 1982.

Twain is evaluated consciously or unconsciously in relation to Eero

Saarinens Gateway Arch (1965), the iconic expression of monumentality and

aspiration that synthesizes a legendary contribution to westward expansion with

an optimistic future. The Arch inaugurated gleaming stainless steel as the

material of choice for public sculpture. Located ten blocks to the west and in full

view of it, and made of a material that if anything was associated with urban

decay, Twain from the outset found

itself in an unwinnable beauty contest

with the Arch. Twain engages the Arch

directly through alignment, a juxtaposition that yields profound symbolism. By

shape and material, the Arch is gendered feminine and Twain masculine, but the more productive realization is that geometrically,

each can accommodate the form of the other.

Moreover, Twains directional

thrust through the apex towards the Arch, deliberately opposing westward

progression (the theme of the Gateway Mall), creates a powerful metaphor for reciprocal longing. Following

Sartwell and Scarry, we might ask what might be the object of such longing. Taking

Scarry further, this metaphor moves us beyond issues of taste into the sphere

of morality, since, as already shown, Twains

beauty (or lack thereof) and the Archs definitive statement of it, can be

clearly linked with political and moral issues.

The complementarity

heightens the poignancy of both the Arch and Twain, but it especially dramatizes Twain as ugly, even threatening. Along with the decay of the urban

core, Twain evokes homelessness

(touched off by derelicts inhabiting the structure and using it as a urinal - La [sic] Grand Pissoir, in the words

of one graffiti writer). In addition, its enclosure can engender feelings

(fantasies) of entrapment, and the record shows that fear and danger are common

associations, even though there is scant evidence of crime against individuals

on the Twain block. Twains engagement of such issues

provides a counterpoint to the one-sided and facile belief in the promise

encoded in the Arch. Earthbound, horizontal, disfigured Twain relieves the unfettered optimism evinced by the soaring

modernist statement of perfection (stainlessness) in form and materials. Furthermore,

the reciprocity with the Arch can be understood in the way the interrogation of

Twain spills over onto the Arch, bringing

to light issues that cloud its history--the Arch came at a price which included

the destruction of low-income neighborhoods on the riverfront, the displacement

of their residents (perhaps to the ersatz shelter provided by Twain), and the partition of the riverfront

from the rest of downtown. Twains

perceived ugliness also produced a metaphor for the imposition of private taste

in the public domain. Whereas sectors of the public wanted monumental art to be

figural and uplifting as part of a city-wide beautification effort, Twains commissioners selected abstraction

of a kind being touted nationally and internationally as the art of the

moment. Abstraction per se was not

objectionable as is clear from the embrace of Saarinens Arch. Had the sculpture on the Twain block achieved consensus on aesthetic merit, there would have

been no outcry about the colonization of public spaces by the art elites of the

city.

The Arch reminds us

of the transformative power of beauty.

Saarinen synthesized the aspirations of generations past and future in

an exquisite form that arose from urban decay.

As a counterweight, Twains

radioactive potential functions as an impediment to forgetting. We could erase

the graffiti, cut the grass, add comfort with benches placed strategically on the block, but Twain

can never succumb to the cartoons demands for something beautiful. Its

beauty lies rather in its capacity to precipitate discourse.

[For more pictures of Twain click here]