|

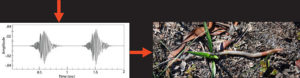

For generations people living around the Appalachicola National Forest have collected earthworms using a mysterious technique called “worm grunting.” Gary Revell (left) – an expert worm grunter – demonstrates the technique at the annual “worm-gruntin” festival in Sopchoppy Florida. A stake is pounded into the ground and rubbed with a flat piece of iron. Each stroke produces strong vibrations that cause hundreds of large worms to come to the surface (Movie). |

|

||

| Vibrations caused by Gary’s worm grunting technique recorded with a geophone. | A large, native earthworm (Diplocardia mississippiensis) emerges from the ground to flee across the surface. | |

| Audrey Revell (right) collects the worms that will later be sold for bait. |  |

| Why do worms emerge from the ground in response to vibrations? This was a long-standing mystery with two common explanations. Some people suggested worms might interpret the vibrations as rain and flee to the surface to avoid drowning. Another explanation, orginally proposed by Charles Darwin, was that worms interpret vibrations as the sound of an approaching mole – a major predator for earthworms.

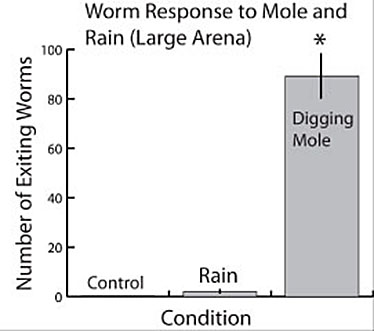

Experiments show that Darwin’s idea was correct. There is a very large population of moles living in and around the Appalachicola National Forest, and the worms flee to the surface when a digging mole is present. In contrast, they do not emerge in response to rain. |

|

| One of many mole tunnels that has been dug across a road in the Appalachicola National Forest (left). The Eastern American Mole (Scalopus aquaticus) is the only species native to the area (right). |

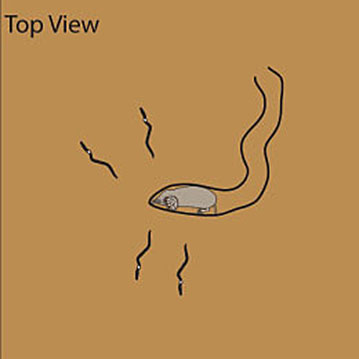

Diagram showing the experimental chamber used to determine how worms respond to a burrowing mole (Movie). |

Results showing the number of earthworms that emerged in response to rain (middle) or a burrowing mole (far right). |

|